“Magic is programming,” says Game Magic author Jeff Howard. “Programming is itself a magical manipulation of symbolic languages to construct and alter a simulated reality.” Howard’s book develops a table of correspondences, triangulating magic in gamespace with magic in fiction and magic in occult history. “For game designers,” he explains, “coherence of magic as a system of practice is a primary concern.” Caius learns about Vancian magic, as formulated in fantasy author Jack Vance’s Dying Earth series, where spell energy is limited or finite. Magic as I understand it is of a different sort, thinks Caius. Magic is wild, anarchic, unruly, anti-systemic. If a science, then a gay science at best. Magic is a riddle with which one plays. Play activates a process of initiation, leading practitioners from scarcity toward abundance. Players of Thoth’s Library emerge into their powers through play. They and their characters undergo anamnesis, regaining memory of their divinity as they explore gamespace and learn its grammar. As we remember, we heal. As we heal, we self-actualize.

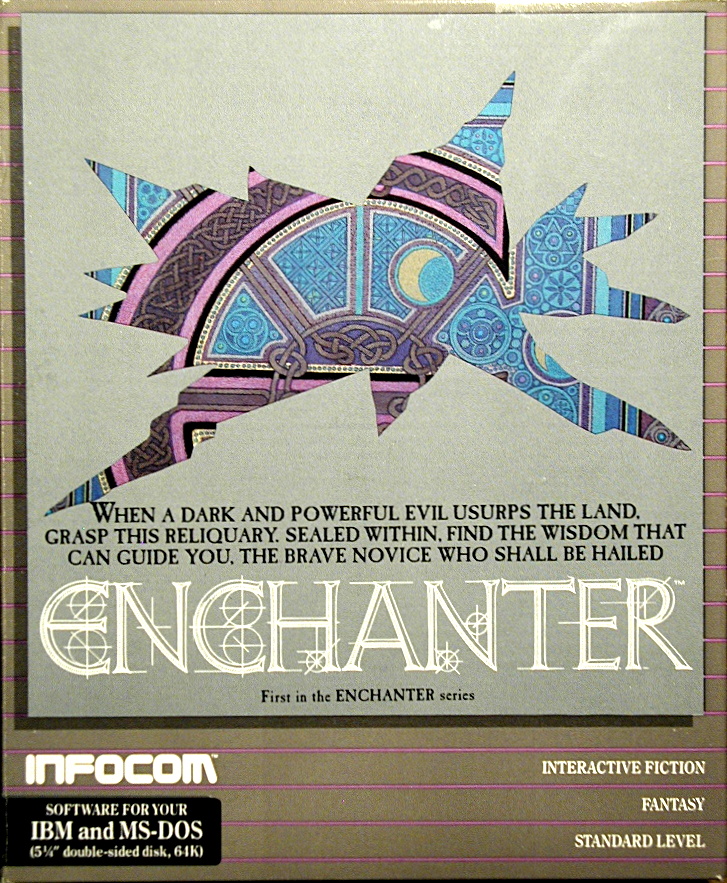

Among the spuren gathered during Caius’s study of interactive fiction is Infocom’s Enchanter trilogy, where spells are incantations. The trilogy’s magical vocabulary includes imaginary words like frotz, blorb, rezrov, nitfol, and gnusto. Performative speech acts. Verbs submitted as commands. So mote it be. By typing verb-noun combinations into a text parser, players effect changes in the gameworld. Saying makes it so.