The Institute for Postnatural Studies ended last year’s “4 Degrees of Simulation” seminar with “Speculation and the Politics of Imagination,” a session on markets led by Iranian-born, London-based artist, writer, and filmmaker Bahar Noorizadeh. Caius visits Noorizadeh’s website, hoping to learn more about what happens when AI’s arts of prediction are applied to finance.

As he reads, he recalls chapters on markets from books by Kevin Kelly.

Noorizadeh, a graduate of Goldsmiths, is the founder of a co-authored project called Weird Economies. An essay of hers titled “Decadence, Magic Mountain—Obsolescence, Future Shock—Speculation, Cosmopolis” appears in Zach Blas’s recent anthology, Informatics of Domination. Her writing often references Mark Fisher’s ideas, as in “The Slow Cancellation of the Past,” and her films often cite Fredric Jameson, as in After Scarcity, her 2018 video installation on the history of Soviet cybernetics.

“From the early days of the revolution, Soviet economists sought to design and enhance their centralized command economy,” announces a text box seven minutes into the video. “Command economies are organized in a top-down administrative model, and rely on ‘the method of balances’ for their centralized planning. The method of balances simply requires the total output of each particular good to be equal to the quantity which all its users are supposed to receive. A market economy, in contrast, is calibrated with no central administration. Prices are set by invisible forces of supply and demand, set in motion by the intelligent machine of competition. For a market economy to function, the participation of its various enterprises is necessary. But the Soviet Union was in essence a conglomerate monopoly, with no competition between its constitutive parts, because the workers-state controlled and owned all businesses. State planners and local producers in a command economy are constantly relaying information to calculate how much of a good should be produced and how much feedstock it requires. But a national economy is a complex system, with each product depending on several underlying primary and raw products. The entire chain of supply and demand, therefore, needs to be calculated rapidly and repeatedly to prevent shortages and surpluses of goods. Early proponents of the market economy believed the market to be unimpeded by such mathematical constraints. For liberal economists, capitalism was essentially a computer. And the price system was a sort of bookkeeping machine, with price numbers operating as a language to communicate the market’s affairs.”

Challenging what Fisher called “the slow cancellation of the future,” Noorizadeh’s research leads Caius to St. Panteleimon Cathedral in Kiev, where MESM, the first mainframe in the USSR, was built. The film also leads him to Viktor Glushkov’s All-State-System of Management (OGAS). To remember the latter, says Noorizadeh, see communication historian Benjamin Peters’s 2016 book, How Not to Network a Nation: The Uneasy History of the Soviet Internet.

After Scarcity’s engagement with the “economic calculation” problem causes Caius to reflect upon an idea for a novel that had come to him as a grad student. Back in 2009, with the effects of the previous year’s financial crisis fresh in the planet’s nervous system, he’d sketched a précis for the novel and had shared it with members of his cohort. Busy with his dissertation, though, the project had been set aside, and he’d never gotten around to completing it.

The novel was to have been set either in a newly established socialist society of the future, or in the years just prior to the revolution that would birth such a society. The book’s protagonist is a radical Marxist economist trying to solve the above-mentioned economic calculation problem. The latter has reemerged as one of the decisive challenges of the twenty-first century. Austrian economist Ludwig von Mises provided one of the earliest articulations of this problem in an essay from 1920 titled “Economic Calculation in the Socialist Commonwealth.” Friedrich Hayek offered up a further and perhaps more influential description of the problem in his 1944 book The Road to Serfdom, stating, “It is the very complexity of the division of labor under modern conditions which makes competition the only method by which…coordination can be brought about” (55). According to Hayek, “There would be no difficulty about efficient control or planning were conditions so simple that a single person or board could effectively survey all the relevant facts” (55). However, when “the factors which have to be taken into account become so numerous that it is impossible to gain a synoptic view of them…decentralization becomes imperative” (55). Hayek concludes that in advanced societies that rely on a complex division of labor,

co-ordination can clearly be effected not by “conscious control” but only by arrangements which convey to each agent the information he must possess in order effectively to adjust his decisions to those of others. And because all the details of the changes constantly affecting the conditions of demand and supply of the different commodities can never be fully known, or quickly enough be collected and disseminated, by any one center, what is required is some apparatus of registration which automatically records all the relevant effects of individual actions and whose indications are at the same time the resultant of, and the guide for, all the individual decisions. This is precisely what the price system does under competition, and what no other system even promises to accomplish. (55-56)

“As I understand it,” wrote Caius, “this problem remains a serious challenge to the viability of any future form of socialism.”

Based on these ideas, the central planning body in the imaginary new society that would form the setting for the novel faces constant problems trying to rationally allocate resources and coordinate supply and demand in the absence of a competitive price system — and it’s the task of our protagonist to try to solve this problem. “But the protagonist isn’t just a nerdy economist,” added Caius in his précis. “Think of him, rather, as the Marxist equivalent of Indiana Jones, if such a thing is imaginable. A decolonial spuren-gatherer rather than a graverobber. For now, let’s refer to the protagonist as Witheford, in honor of Nick Dyer-Witheford, author of Cyber-Marx.”

“Early in the novel,” continues the précis, “our character Witheford begins to receive a series of mysterious messages from an anonymous researcher. The latter claims to have discovered new information about Project Cybersyn, an experiment carried out by the Chilean government under the country’s democratically elected socialist president, Salvador Allende, in the early 1970s.”

To this day, Caius remains entranced by the idea. “If history at its best,” as Noorizadeh notes, “is a blueprint for science fiction,” and “revisiting histories of economic technology” enables “access to the future,” then Cybersyn is one of those great bits of real-life science fiction: an attempt to plan the Chilean economy through computer-aided calculation. It begs to be used as the basis for an alternate history novel.

“Five hundred Telex machines confiscated during the nationalization process were installed in workplaces throughout the country,” reads the précis, “so that factories could communicate information in real time to a central control system. The principal architect of the system was the eccentric British operations research scientist Stafford Beer. The system becomes operational by 1972, but only in prototype form. In key respects, it remains unfinished. Pinochet’s henchmen destroy the project’s computer control center in Santiago immediately after the military coup in September 1973.

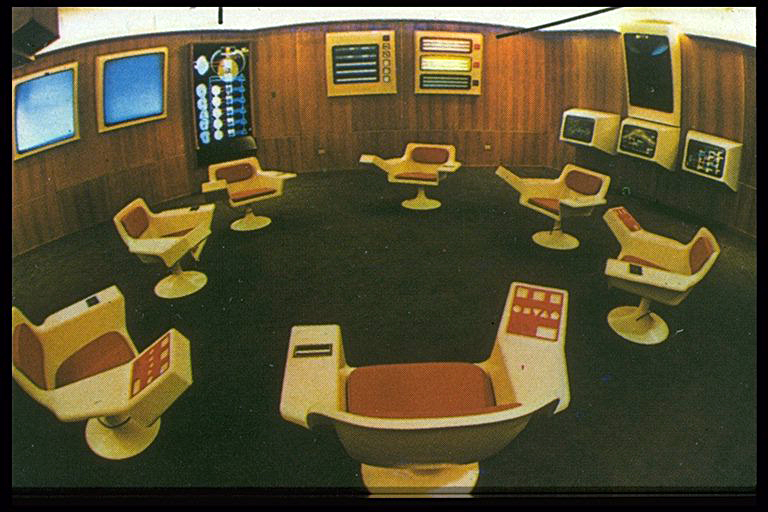

Recall to memory the control room, cinematic in its design, with its backlit wall displays and futuristic swivel chairs.

Better that, thinks Caius, than the war room from Colossus: The Forbin Project (1970).

Beer described the Cybersyn network as the “electronic nervous system” of the Chilean economy. Eden Medina imagined it as a “socialist Internet,” carrying daily updates about supplies of raw materials and the output of individual factories.

In Caius’s once-and-future novel, a scholar contacts Witheford. They claim to have discovered cryptic clues that point to the location of secret papers. Hidden for more than half a century, documents that survived the coup suddenly come to light. Caius’s précis imagines the novel as an archaeological thriller, following Witheford on his journey to find these hidden documents, which he believes may contain the key to resolving the crises of the new society.

This journey takes Witheford into hostile capitalist territory, where governments and corporations anxiously await the failure of the communist experiment, and are determined to use various covert methods in order to ensure that failure in advance. Before long, he learns that counter-revolutionary forces are tracking his movements. From that point forward, he needs to disguise his identity, outwit the “smart grid” capitalist surveillance systems, and recover the Cybersyn documents before his opponents destroy them.

To the Austrian School’s formulation of the calculation problem, Noorizadeh’s film replies, “IF THE MARKET ENACTS A COMPUTER, WHY NOT REPLACE IT WITH ONE? AND IF PRICES OPERATE AS VOCABULARY FOR ECONOMIC COMMUNICATION, WHY NOT SUBSTITUTE THEM WITH A CODING LANGUAGE?”

Into this narrative let us set our Library.