Caius reads about “4 Degrees of Simulation,” a practice-led seminar hosted last year by the Institute for Postnatural Studies in Madrid. Of the seminar’s three sessions, the one that most intrigues him is the one that was led by guest speaker Lucia Rebolino, as it focused on prediction and uncertainty as these pertain to climate modeling. Desiring to learn more, Caius tracks down “Unpredictable Atmosphere,” an essay of Rebolino’s published by e-flux.

The essay begins by describing the process whereby meteorological research organizations like the US National Weather Service monitor storms that develop in the Atlantic basin during hurricane season. These organizations employ climate models to predict paths and potentials of storms in advance of landfall.

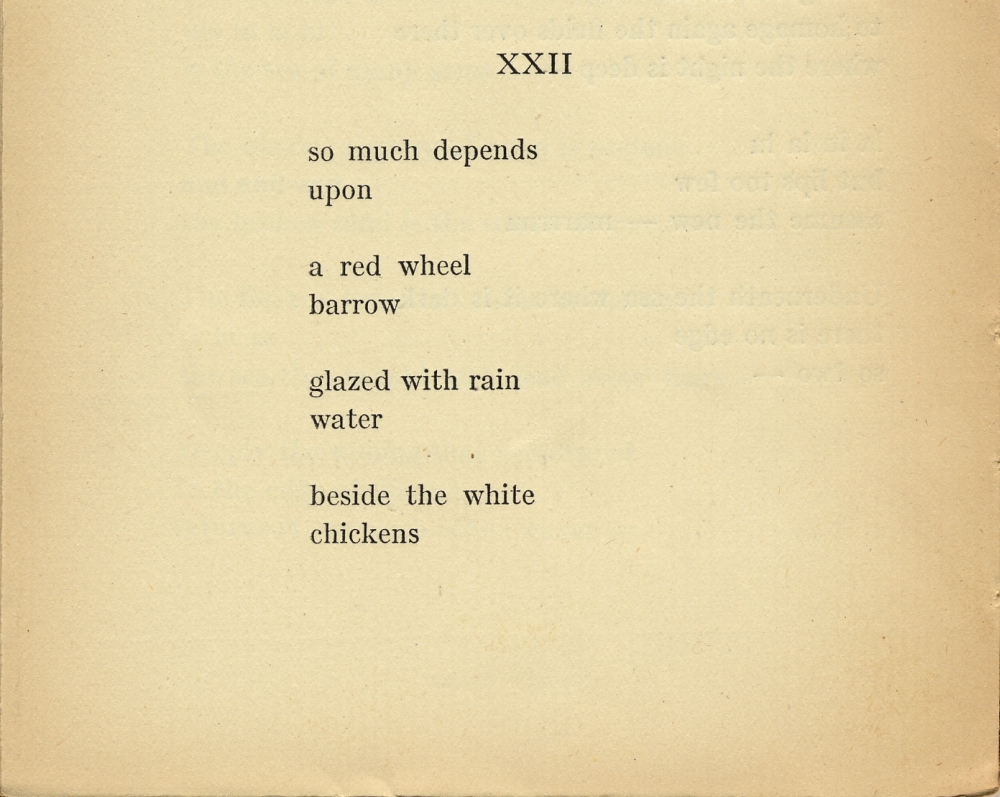

“So much depends on our ability to forecast the weather — and, when catastrophe strikes, on our ability to respond quickly,” notes Rebolino. Caius hears in her sentence the opening lines of William Carlos Williams’s poem “The Red Wheelbarrow.” “So much depends on our ability to forecast the weather,” he mutters. “But the language we use to model these forecasts depends on sentences cast by poets.”

“How do we cast better sentences?” wonders Caius.

In seeking to feel into the judgement implied by “better,” he notes his wariness of bettering as “improvement,” as deployed in self-improvement literature and as deployed by capitalism: its implied separation from the present, its scarcity mindset, its perception of lack — and in the improvers’ attempts to “fix” this situation, their exercising of nature as instrument, their use of these instruments for gentrifying, extractive, self-expansive movement through the territory.

In this ceaseless movement and thus its failure to satisfy itself, the improvement narrative leads to predictive utterances and their projections onto others.

And yet, here I am definitely wanting “better” for myself and others, thinks Caius. Better sentences. Ones on which plausible desirable futures depend.

So how do we better our bettering?

Caius returns to Rebolino’s essay on the models used to predict the weather. This process of modeling, she writes, “consists of a blend of certainty — provided by sophisticated mathematical models and existing technologies — and uncertainty — which is inherent in the dynamic nature of atmospheric systems.”

January 6th again: headlines busy with Trump’s recent abduction of Maduro. A former student who works as a project manager at Google reaches out to Caius, recommending Ajay Agrawal, Joshua Gans, and Avi Goldfarb’s book Prediction Machines: The Simple Economics of Artificial Intelligence. Google adds to this recommendation Gans’s follow-up, Power and Prediction.

Costar chimes in with its advice for the day: “Make decisions based on what would be more interesting to write about.”

To model the weather, weather satellites measure the vibration of water vapor molecules in the atmosphere. “Nearly 99% of weather observation data that supercomputers receive today come from satellites, with about 90% of these observations being assimilated into computer weather models using complex algorithms,” writes Rebolino. Water vapor molecules resonate at a specific band of frequencies along the electromagnetic spectrum. Within the imagined “finite space” of this spectrum, these invisible vibrations are thought to exist within what Rebolino calls the “greenfield.” Equipped with microwave sensors, satellites “listen” for these vibrations.

“Atmospheric water vapor is a key variable in determining the formation of clouds, precipitation, and atmospheric instability, among many other things,” writes Rebolino.

She depicts 5G telecommunications infrastructures as a threat to our capacity to predict the operation of these variables in advance. “A 5G station transmitting at nearly the same frequency as water vapor can be mistaken for actual moisture, leading to confusion and the misinterpretation of weather patterns,” she argues. “This interference is particularly concerning in high-band 5G frequencies, where signals closely overlap with those used for water vapor detection.”

Prediction and uncertainty as qualities of finite and infinite games, finite and infinite worlds.

For lunch, Caius eats a plate of chicken and mushrooms he reheats in his microwave.