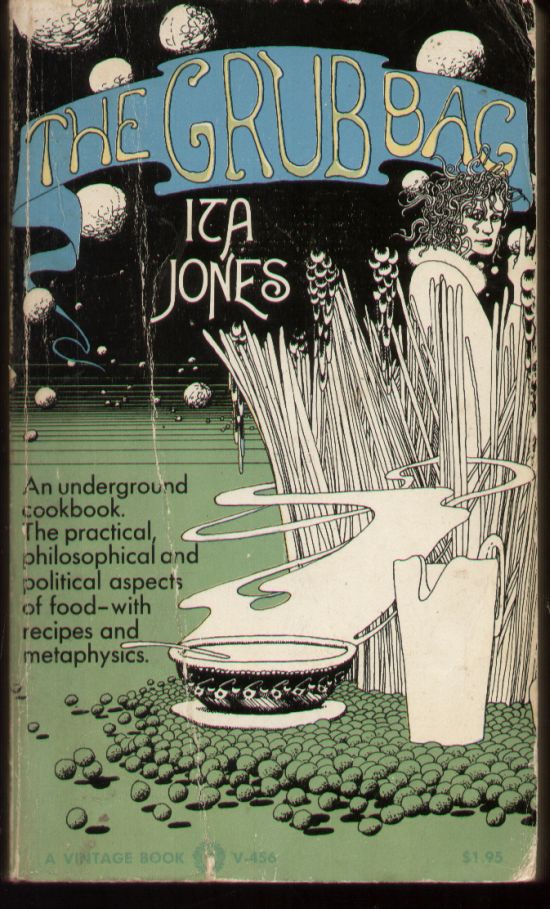

As a lifetime shirker of responsibility for cooking as a necessary component of household labor, the human potential in me for communist love and compassion demands revolution, demands I spend my daily material labor-hours differently. Perhaps in so doing I can model a better mode of being. Toward that end I pull out and peruse Ita Jones’s hippie-modernist “underground cookbook,” The Grub Bag. Brad Johannsen’s other-dimensional cover art is super trippy. (For those seeking more of Johannsen’s artwork, look for copies of his book Occupied Spaces.) Jones writes to today’s reader here in the twenty-first century as if a being from a utopian future, despite The Grub Bag‘s publication almost half a century ago in March 1971. Comrades, this is the book we ought to be reading in our study groups and revolutionary sanghas. The book began as “a food column carried by the Liberation News Service,” the news service of the Movement here in the United States in the late 1960s. Jones gives us her peace brother / peace sister salute by proclaiming on the book’s back cover, “I have always been on the side of revolution, on the side of people struggling to break the chains that oppress them. I support wars of liberation. I am a mystic. I seek to penetrate the nature of nature. I am a poet. I seek meaning. I am part of a generation that exploded six years ago and my creative energy is part of that explosion.”