How is it that both the United States and China hosted movements of urban youth to rural areas, “back to the land” in the one, “down to the countryside” in the other, to such vastly different effects? Let us care for life in all its forms, including the form it took in Dirt Road to Psychedelia, a film about Austin, TX in the 1960s. The radical comix artist Gilbert Shelton emerged from that scene, as did Roky Erickson and Janis Joplin. The documentary reinstates in consciousness lesser-known classics, like Take Me to the Mountains by Shiva’s Headband. My pedagogy begins by offering students collective power-sharing and shared ownership in the classroom. Once a class collaborates on revision of the syllabus, they’ve become co-creators of reality. Class consciousness foments and rises. They witness their vast and previously unrealized collective capacities.

Category: Uncategorized

Thursday January 17, 2019

The second part of the 1990 documentary Berkeley in the Sixties is titled “Confronting America.” After the victory of the Free Speech movement on the Berkeley campus, the world transforms from black-and-white to color. Students decide to commit themselves to naming and controlling the system, else it destroy the world. They start to change: new ideas, new music, new hair, new groups, new consciousness. The counterculture enters the equation. More and more people start to turn on. They start to gather and collaborate in liberated territories. They march, they don helmets, they defend themselves from attacks by police. This gives way to “Part Three: Confronting History,” where armed revolutionary organizations like the Black Panthers step onstage and revolutionary confrontations occur in France, Japan, Mexico, and Czechoslovakia. “So much life, so much death,” as Michael Rossman notes in retrospect, “so much possibility, so much impossibility.” Now that all of these kids are at the table, what happens next? How do we let ourselves go and speak freely? How do we deactivate internal censors? Sons of Champlin sing in reply, “Get High.” Lovely midsection built around bells and vibes. Out of it we emerge giggling, “Where are we?” This new dawn looks fantastic. My students are bright and interesting. We spent the day together deconstructing and rebuilding our classroom in the spirit of power-sharing egalitarianism. The air feels rich with possibility. A voice speaks up and teaches, “Open doors, look around you: we’ve all been blessed with wings!”

Wednesday January 16, 2019

Life unfolds in installments of day and night. For work I review the documentary Berkeley in the Sixties, a film I’ve watched and taught many times over the years. The first section of the film is titled “Confronting the University.” Berkeley President Clark Kerr appears before an audience attempting to rebrand the public university as an appendage of the “knowledge industry” and a focal point of fiscal growth for the state economy. Against him rise students like Jack Weinberg and Jackie Goldberg, young people who arrived to the university looking for truth and meaning. The university came to operate for them and for the other members of the Free Speech movement as a site for live, immediate, direct, hands-on transformation of society. As viewers we watch with some surprise as the movement succeeds in growing and repeatedly mobilizing a large coalition of members. The “children of affluence,” the future managers of the society realize in the thousands that their education has been designed to ruin them. The battle over free speech evolves into something more generalizable, something much more meaningful and appealing: a battle against dehumanization. The war of humanity against unchecked bureaucracy. Students at Berkeley made the radical choice to live, to revolt, to actively push back and participate in co-creation of the future through occupation of buildings. They gather in the agora of the auditorium and laugh and boo at and surround and confront the bald head of the head of the university, President Kerr. They talk about sitting down together and re-planning the whole structure of the university with a new conception of the purpose of education. They realize that the mechanisms that the Free Speech movement attempted to change are mechanisms operating throughout the society. As audience members, we realize the same is true today. Their story thus confronts us with the question, “What would WE say, how would WE behave, if we abolished hierarchy and suspended authority? What if we did that, here and now, in our classrooms?”

Tuesday January 15, 2019

Listening closely, entertaining a variety of interpretations as possibilities running simultaneously beside one another, I wander, first among the hallways of David Bowie’s “Memory of a Free Festival,” already a bit distant and nostalgic, the gathering recalled in past tense: “It was…It was…It was.”

Bowie’s lyrical persona sings from Milton territory — trying to reconstitute hope amid summer’s end, paradise lost. By song’s end, distant festival-goers join voices in a chorus of reconciliation, animated by the sentiment, “The Sun Machine is Coming Down, and We’re Gonna Have a Party.” Afterwards, I re-watch Easy Rider, noting the semantic riches of the film’s opening shot of a trompe l’oeil mural of pre-Conquest Mexico on the side of a pit-stop called La Contenta Bar in Taos, New Mexico. The scene depicts US-Mexican relations in terms of the black-market capitalist exchange-relation of the drug deal. The Captain and Billy are just small-timers, their counterculture a mere cargo cult, the film notes in the next scene, where the two men crouch defensively as the planes of the global techno-capitalist superpower fly overhead. Look at Peter Fonda loading his bike’s American flag embroidered fuel tank with rolls of dollars as Steppenwolf sings “The Pusher.” He and Hopper walk like natives of the space age among desert farmhouse ruins. They seem as alien to these landscapes as their motorbikes — products of a different stage of development. The bikes make the horses of white settler-colonialist ranchers skittish. The Captain pays respect by complimenting the ranchers on their “spread.” “You do your own thing on your own time: you should be proud.” Hippies appear here as mere nouveau riche speculators eyeing potential property on the frontier. The montage sequence that accompanies “The Weight” is an ode to the magic of the deserts of the American Southwest. Passing a joint back and forth with a paisley-bandana’d hitchhiker, Captain and Billy learn of the disrespectful nature of their colonial heritage. After soaking it in, the Captain asks the others if they’ve ever wished they were someone else. The same theme reemerges later in the film. After smoking his first joint around a campfire on the way to Mardi Gras, Jack Nicholson’s character George Hanson comes alive with far-out tales of aliens from a more advanced civilization living among Americans since 1946. Both he and the Bowie of “Memory of a Free Festival” refer to these figures as “Venusians.” By the end of the film, though, I’m left wondering: Are Captain and Billy victims of a Faustian bargain, as J.D. Markel argues, following the path of Dante’s Inferno?

Monday January 14, 2019

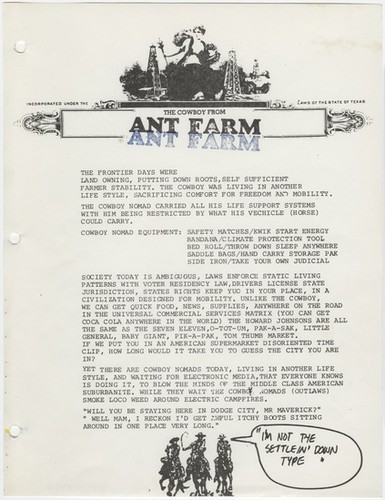

I wish there was time to fit radical media theorist Gene Youngblood’s book Expanded Cinema into my course on Hippie Modernism. Youngblood’s work shares in the cosmic consciousness whipped up by the two big events of the Summer of ’69, Woodstock and the moon launch. For Abbie Hoffman, remember, Woodstock served as a mind-blowing demonstration of “Functional anarchy, primitive tribalism, gathering of the tribes.” Youngblood’s book examined the role participatory media events and media revolution might play in this project. The main prerequisites to demonstrate the human capacity for psychedelic beloved community were all present at Woodstock: willingness to live side by side in harmony, feeding and caring for one another, with no expectation of profit. Another version of the utopian hippie modernist Woodstock Nation of the future can be glimpsed in Ant Farm’s Cowboy Nomad manifesto from 1969. One can imagine dozens of Woodstocks scaling up into Ant Farm’s Truckstop Network, tribes traveling in caravans of camper vans and VW buses.

Sunday January 13, 2019

It is my job, my duty and responsibility, to help youth remember the experiments of past generations of liberationist youth. My hope is that by these means, students may gain a fuller understanding of seeds planted, potentials as yet unrealized. Let us learn all that was learned before, and somehow try again. My friend’s father — a kind of shaman, one who initiated me into a secret universe — once starred in a grand movie production, a collective 3-day performance of peace, love, and music known as Woodstock. “Climb close, listen here,” he told me a few nights ago over dinner. “The conditions were terrible,” he began, “yet love prevailed.” Grace Slick navigated her way to stage and announced, “Alright, friends, you have seen the heavy groups, now you will see morning maniac music. Believe me, yeah — it’s a new dawn.” Soon they’ve launched into “Won’t You Try / Saturday Afternoon,” the band’s homage to the Summer of Love. When John Sebastian takes the stage in beautifully tie-dyed denim, he reflects back to the community of 300,000 its image of itself as an impromptu city, a temporarily autonomous global village. The lyrics to Sebastian’s “Younger Generation” speak sounds of accord into my present moment. Country Joe rouses the entire city to its feet in opposition to the War in Vietnam. Sly & The Family Stone arrive like angels and take the crowd heavenward, peace signs in the sky, voices raised in song. By the time of Hendrix’s performance, one realizes one is in the presence of peaceful visitation by starmen of the future. Enough! Let’s get ourselves back to the garden, as Crosby, Stills & Nash instruct in the film’s finale, “Woodstock.”

Friday January 11, 2019

Michael Wadleigh’s Woodstock (1970), co-edited by a young Martin Scorsese, overlays sounds and images, especially in its use of split-screen, in order to represent the crowd as a cooperative beloved community. The collective intelligence of audience, performers, and crew is astounding, comparable only to that other collective intelligence, the US military. With the walkie-talkies and the helicopters and the ever-present talk of food and supplies, the festival was clearly the War in Vietnam’s deliberately inverted double.

Thursday January 10, 2019

M.C. Richards writes of her debt to certain techniques and strategies of high and late modernism toward the end of Centering. (It’s perhaps more than a mere coincidence, I think to myself as I write this, that Jimi Hendrix’s song “Voodoo Child” shares initials with the US military’s enemy at the time the song was released in October 1968, the Viet Cong.) “I have lived my life close to certain impulses in contemporary art,” writes Richards. “The music of the single sound, the composition of silence, and proliferating galaxies. The poetics of Western Imagism — ‘no ideas but in things.’ Garbage art: sculpture out of mashed automobiles; paintings out of old Coke bottles, soiled shirts, window blinds, coat hangers; paintings made out of dirt meant to look like dirt, to consecrate the dirt; an art which consecrates the discard. Cellar doors, walls, sidewalks, street surfaces: as well as all the minutiae of nature. A choreography of making breakfast. Summoning attention, drawing the gaze in, into. And into the wonder comes a kind of high mirth. A release of joy in the form” (Centering, p. 144). Writing becomes for Richards a transcription of her thoughts as she attends to the conditions by which she thinks.

Wednesday January 9, 2019

After a nap in a park under a sunny blue January sky, Parliament helps me loosen up and release stress I’ve been carrying in my shoulders, neck, and upper back. Time to blow the cobwebs from my mind with the Mothership Connection. That is where I’m at and it feels good.

P-Funk had its own mythology. George Clinton performed at times as his messianic alien alter-ego, Star Child. My first encounters with “Mothership Connection” came by way of Dr. Dre’s sample of it on “Let Me Ride” from his debut solo album The Chronic, released the year of my fourteenth birthday. Robin D.G. Kelley discusses artists like Parliament-Funkadelic and Sun Ra’s Afrofuturist brand of hippie modernism in his book Freedom Dreams. These were artists who “looked backward to look forward, finding the cosmos by way of ancient Egypt.” I love the idea of a revolution you join by putting “a glide in your stride and a dip in your hip,” projecting one’s body here and now into a 3-D realtime utopian Afrofuturist “world within the world” known as the Mothership. The P-Funk song’s reference to the famous spiritual “Swing Low Sweet Chariot,” used by members of the Underground Railroad as a coded form of communication to help people escape, reminds me of the Trystero group’s use of the posthorn symbol in Thomas Pynchon’s The Crying of Lot 49. Other P-Funk tracks are also worthy of analysis and comment. The early Funkadelic song “Can You Get To That,” for instance, alludes to Dr. Martin Luther King’s “Dream” speech with its metaphor of the bounced check.

“America has given the negro people a bad check,” King intoned, “a check which has come back marked insufficient funds.” This stuff definitely ought to find its way into my course this semester — as should the work of jazz poet Ted Joans and illustrator Pedro Bell. The latter created the liner art for several key P-Funk releases. As George Clinton notes on his official website, “What Pedro Bell had done was invert psychedelia through the ghetto. Like an urban Hieronymus Bosch, he cross-sected the sublime and the hideous to jarring effect. Insect pimps, distorted minxes, alien gladiators, sexual perversions. It was a thrill, it was disturbing. Like a florid virus, his markered mutations spilled around the inside and outside covers in sordid details that had to be breaking at least seven state laws. […]. He single-handedly defined the P-Funk collective as sci-fi superheroes fighting the ills of the heart, society and the cosmos.”

Tuesday January 8, 2019

As a kind of essayist — one who writes to think, to find out, to endeavor — I often look for meaning, associations, correspondences, in that upon which I gaze. A friend lends a note of caution: some of what we find, he reflects, might be projected, phantasmatic rather than cloud-hidden. Of course, fantasies are not purely illusory. Psychoanalysts encourage us to think of them, rather, as scenes that stage unconscious desires. Lacan reads fantasy as a defensive formation assembled by a subject to veil the enigmatic desire of the Other. Fantasy hastens an answer to what can never be known, like one’s face or the back of one’s head, that which can never enter directly into the field of one’s perception. Fantasy pretends to solve what Lacan calls the mystery of “Che vuoi”: “What do others want from me? What do they see in me? What am I for others?”