Twitter is a “wit” platform. The platform dictates a literary style of hot takes and witticisms: outrage delivered with brevity and snark.

Sunday February 28, 2021

A neighbor with a chainsaw helps me remove a fallen tree. He relays the yard’s history, helps us decipher the boundaries of a garden, one he tended in years past. He’s a contractor. A worker who works with him brought music and, with a wheelbarrow, lent a hand removing the tree. To both the worker and the neighbor, I am thankful. Yellow daffodils sprout around the house and in the yard. I imagine plucking a sprout of onion grass and eating it as seasoning atop a baked potato. This I do.

Friday February 26, 2021

I met with a therapist yesterday. He posed questions and we spoke. My insurance doesn’t cover this treatment, so at the end of an hour, I pay a fee. I’m thus paying again for a service, as I did as a student. Given the debt I’ve accrued, I can only endure the therapeutic relationship temporarily. I can’t afford for it to continue beyond a few sessions. For those few sessions, though, let us exercise trust. Assume the path ahead an opportunity to speak and heal through conversation with a fellow head. Allow in the weeks ahead time for reinvestigation of psyche. Talking time. Speech practices. Adventures in neuroplasticity. Speaking of which: I imagine I could benefit from a re-encounter with French philosopher Catherine Malabou. I imagine, I imagine. Yet there is much to do. Consult with the Book of Job and be reminded, “the price of wisdom is above rubies.” Consult with “Deep Deep Dream,” an experiment from Ignota Books, and confront a question posed by a future epoch “now, in the present”: Audio or Visuals? Consult with David Crosby and be reminded of a child laughing in the sun.

Monday February 22, 2021

The remains of a stone retaining wall run like a spine through the yard. “Think of how we might relate to it when we plant our garden,” I tell myself as I admire the wall’s mosses and walk its length. I picture suddenly an amphitheater, and with it, some fantasy of community that would use it. Perhaps it’s time again for some Movement. Tomorrow we join Frankie on her first trip to the zoo.

Sunday February 21, 2021

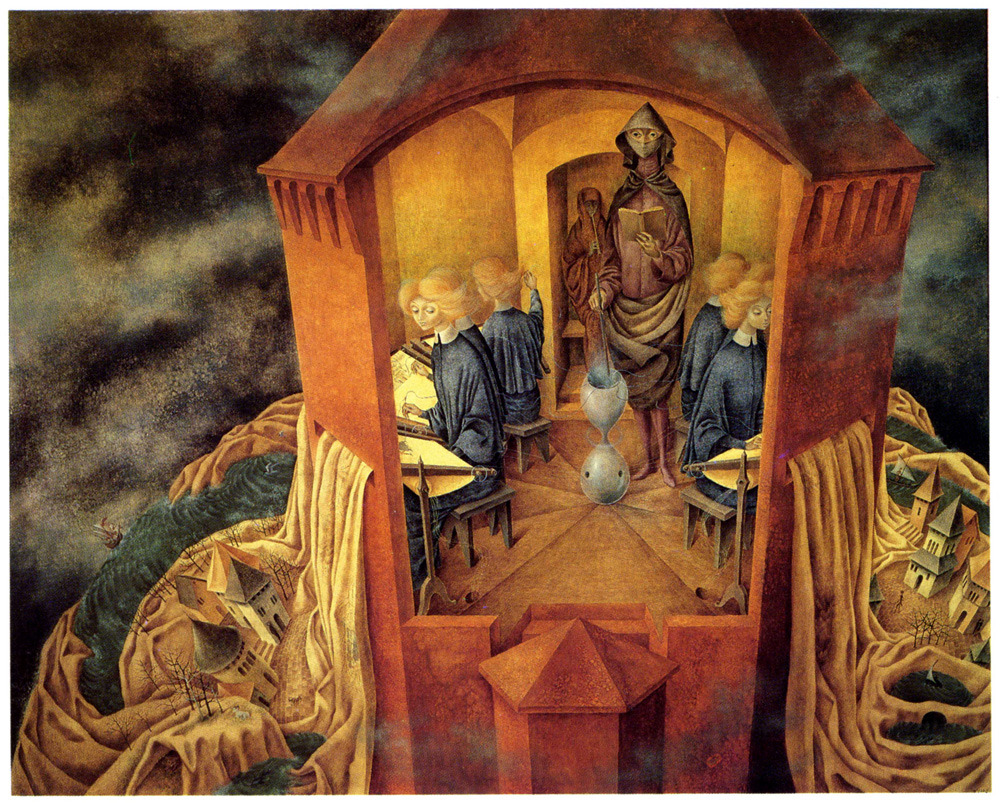

Rereading Freud’s Civilization and Its Discontents, the parent in me wants instantly to refute it. I want for my daughter something other than the Oedipus complex. I imagine a succession of heroines and goddesses. Why among all the characters of mythology does Freud opt for Oedipus and Electra? The latter, of course, has been reinvented in our time as a Marvel superhero. No longer daughter of Agamemnon and Clytemnestra, she wields a pair of sai. Electras loom large in the minds of at least two hideous men: Freud and Frank Miller. What if instead we imagine Oedipa Mass, the heroine in Thomas Pynchon’s novel The Crying of Lot 49? While imagining Oedipa, imagine too the women in “Bordando el Manto Terrestre (“Embroided Earth’s Mantle”),” the Remedios Varo painting (middle part of a triptych, in fact) viewed by Oedipa at a key point in the novel.

The figures in each case are all still figures trapped in another’s tapestry. “Such a captive maiden,” writes Pynchon, “having plenty of time to think, soon realizes that her tower, its height and architecture, are like her ego only incidental: that what really keeps her where she is is magic, anonymous and malignant, visited on her from outside and for no reason at all. Having no apparatus except gut fear and female cunning to examine this formless magic, to understand how it works, how to measure its field strength, count its lines of force, she may fall back on superstition, or take up a useful hobby like embroidery, or go mad, or marry a disk jockey. If the tower is everywhere and the knight of deliverance no proof against its magic, what else?” This, too, is the dilemma faced by Melba Zuzzo, the heroine of Joanna Ruocco’s novel Dan. Next thing I know, I’m sending myself “Playing the Post Card: On Pynchon’s The Crying of Lot 49“ while scanning my shelves for H.D.’s book Tribute to Freud. Having seen the Varo painting in an exhibit a year prior to writing the novel, Pynchon recalls it from memory. Oedipa sees in the painting what Pynchon wants her to see. If she’d looked closely, she’d have seen “La Huida (The Escape),” the third part of the triptych, where the girl and her lover flee to the mountains.

And at the center of the triptych, reading from a spell book and stirring a cauldron, a sorceress. Such figures of power and liberation are occulted by Pynchon’s imagining of a feminized Oedipus — a character “hailed,” “interpellated” as Althusser would say, in the novel’s opening sentence when named executor of the estate of her former lover, Pierce Inverarity. Principle among the items of Pierce’s estate is a stamp collection. LSD is a plot point in Pynchon’s novel. Perhaps we could read Pierce’s stamp collection as the equivalent of “blotter art.” It’s described as containing “thousands of little colored windows into deep vistas of space and time,” and is delivered to Oedipa by “somebody named Metzger.” Readers might be forgiven for confusing “Metzger” with “Metzner,” as in the logic of a dream. As in “Ralph Metzner,” editor of Psychedelic Review and co-author, along with Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert, of The Psychedelic Experience.

Saturday February 20, 2021

Author seats himself and turns on to Funkadelic. “Why is everyone afraid to say ‘Kiss me!'” asks George Clinton on “Mommy, What’s a Funkadelic?,” the 9:04 opener on the band’s debut. It’s a sad song when heard in light of Fred Moten’s comments about the cries of Frederick Douglass’s Aunt Hester, the black variant of Freud’s “primal scene.” Moten argues that those sounds continue; “Joy and Pain,” he says, are integral parts of black music, as in the track by Maze feat. Frankie Beverly, or the Rob Base and DJ E-Z Rock version from 1988. The Funkadelic album is too much, a big ‘ol heap of “way back yonder funk,” “ancient old funk.” I’m reminded — reshaped, resounded — as the album proceeds. A description of “the songs of the slaves” follows the Aunt Hester scene in Douglass’s autobiography — and that’s what I hear when I hear “Music for My Mother.”

Thursday February 18, 2021

Awaiting a therapy session with a gestalt psychologist, I reflect upon psychoanalysis. Coleridge imports the Unconscious into English after study of German philosophy. Freud sets this concept at the center of his project, his newly-founded science, psychoanalysis. The latter attempts a secular-scientific grasping of the Unconscious. Freud had a practice. He was a therapist. He was paid by clients. He treated patients. Psychoanalysis is a technology of the self. The therapist is one who applies a treatment, a cure for individuals suffering new illnesses of modernity: neuroses and psychoses. Before psychoanalysis, treatment of mental illness was a duty performed by clergy, or by “madhouses,” institutions invented by the State. Freud’s “talking cure” is an attempt to heal individuals who, in other times, would have been handed one-way tickets to board Ships of Fools or subjected to some other means of solitude and confinement. Psychoanalysis happened: it was put to use as a state apparatus, it was absorbed into institutions, it became part of the technocratic machinery of Western modernity. The mid-twentieth century was the age of psychoanalysis. The latter shaped the way the century thought itself. Freud fed into the development of public relations and advertising, especially through the influence of his nephew, Edward Bernays. According to French Marxist Louis Althusser, however, these uses were all betrayals of Freud’s revolutionary discovery. “The fall into ideology,” he writes, “began…with the fall of psycho-analysis into biologism, psychologism, and sociologism” (“Freud and Lacan,” p. 191).

Tuesday February 16, 2021

Dereliction of dung heap. Data-driven dumbwaiter at your service. Chronically correct I effect my own cause. Alpha Dog to Omega Man: can you read me? Justin Timberlake’s “What Goes Around…Comes Around” saddens me, so I head outdoors. I gather sticks. I stand among the trees, finding in the sky above me the crescent moon. The night’s songs are sad ones: Dolly Pardon’s “Jolene” and Regina Spektor’s “Fidelity.” And just this morning arrived the words of artist-friend Irving Bleak, speaking of owls as characters in world mythology. Characters in the lives of children. Guardians, protectors. I think of the Tesseract from Madeline L’Engle’s A Wrinkle in Time. Owls appear as a ‘theme’ or ‘motif’ throughout the evening. For work, meanwhile, I’ve had to reconsider Freud. Prep for an upcoming lecture. “Aggressiveness was not created by property,” he asserts in Civilization and Its Discontents. “It reigned almost without limit in primitive times, when property was still very scanty, and it already shows itself in the nursery almost before property has given up its primal, anal form. […]. If we were to remove this factor…by allowing complete freedom of sexual life and thus abolishing the family, the germ-cell of civilization, we cannot, it is true, easily foresee what new paths the development of civilization could take; but one thing we can expect, and that is that this indestructible feature of human nature will follow it there” (61). Aggression is for Freud an “indestructible feature of human nature.” Do those of us with children know otherwise? Freud is a cultural chauvinist, a bourgeois moralist, a critic of communism and an apologist for capitalist imperialism. I think now of his critics: Left Freudians like Herbert Marcuse, but also the Italian Marxist Sebastiano Timpanaro. Most of all, though, I think of anticolonial theorist and psychiatrist Frantz Fanon. How might we put Freud to radical use today amid Black Radical critiques of Western subjectivity and the rise of psychedelic science? I’m reminded of the opening remarks in Slavoj Žižek’s book The Ticklish Subject. “A spectre is haunting Western academia,” he writes, “the spectre of the Cartesian subject. Deconstructionists and Habermasians, cognitive scientists and Heideggerians, feminists and New Age obscurantists — all are united in their hostility to it.” Žižek himself, however, defends the subject — from these and other of its critics. Ever the provocateur. I’m teaching a gen-ed lit course. My task is to introduce Freud to students new to him. Let us establish the subject before we critique it. During breaks from Freud I watch the new Adam Curtis series Can’t Get You Out of My Head (2021) and read bits of Principia Discordia. In whatever book is finally written on acid’s arrival into history, there will be a chapter on Discordianism and Kerry Thornley, “Operation Mindfuck” figuring prominently therein. Colonization of the last free outpost, the human mind.

Sunday February 14, 2021

There have been times in my life when writing is simply an ongoing process, happening alongside other happenings, author scribing in notebook, looking around, listening, learning. Connecting, transmitting. My scale is small. I’m no Vertov. But sometimes life happens in such a way that the hand moves. One evades capture in silence and solitude by conversing with others, mourning the passing of the great free-jazz drummer, gardener-philosopher, and healer Milford Graves. He and Derek Jarman inspire me. To them now I appeal. And like that, with eyes closed, I see the following. A wall of circles like the speakers at the center of the Grateful Dead’s Wall of Sound, the public address system through which they played. “Time fer some music,” shouts an announcer through the speakers. Henry Cow, innit? Aggressively proggy. Sarah arrives and trains me on the air fryer. Hurrah, hurrah. Delivery arrives with sandwiches. Hurrah, hurrah.

Saturday February 6, 2021

Trance-script fed back to the cyber-subject becomes like Tom Phillips’s A Humument: heavily redacted. Synchronicities appear each day pointing ambiguously toward both hope and fear — reality a kind of “waking-dream” therapy. Selection of hopeful passages rather than fearful ones: that’s the task each round, each turn-based move, made easier when we remember that the latter are sweet nuthins. Lou sings it and the subject listens.

that

which

he

hid

reveal I

writes Phillips across his book’s frontispiece. Parquet Courts sings of being “in the chaos dimension / Trapped in a brutal invention.” We don’t want that, do we? So imagine it differently.