Into the Library we welcome Kodwo Eshun: British-Ghanaian writer, theorist, and filmmaker. Self-described “concept engineer.” Key ally of the CCRU, participating in the group’s Afro-Futures event, a 1996 seminar “in which members of the Ccru along with key ally Kodwo Eshun explored the interlinkages between peripheral theory, rhythmic systems, and Jungle/Drum & Bass audio” (CCRU Writings 1997-2003, p. 11). In 1998, Eshun releases More Brilliant than the Sun: Adventures in Sonic Fiction, classic work on the music of Afrofuturism. More recently, founder and member of the Otolith Group.

Eshun devised a unique page-numbering system for More Brilliant than the Sun. The book begins in negative numbers. “For the Newest Mutants,” reads its line of dedication, as if in communication with Leslie Fiedler and Professor X.

As with Plant and Land, Eshun is unapologetically cyberpositive.

“Machines don’t distance you from your emotions, in fact quite the opposite” begins Eshun. “Sound machines make you feel more intensely, along a broader band of emotional spectra than ever before. […]. You are willingly mutated by intimate machines, abducted by audio into the populations of your bodies. Sound machines throw you onto the shores of the skin you’re in. The hypersensual cyborg experiences herself as a galaxy of audiotactile sensations” (More Brilliant than the Sun, p. 00[-002]-00[-001]).

“The bedroom, the party, the dancefloor, the rave: these are the labs where…21st C nervous systems assemble themselves” (00[-001]).

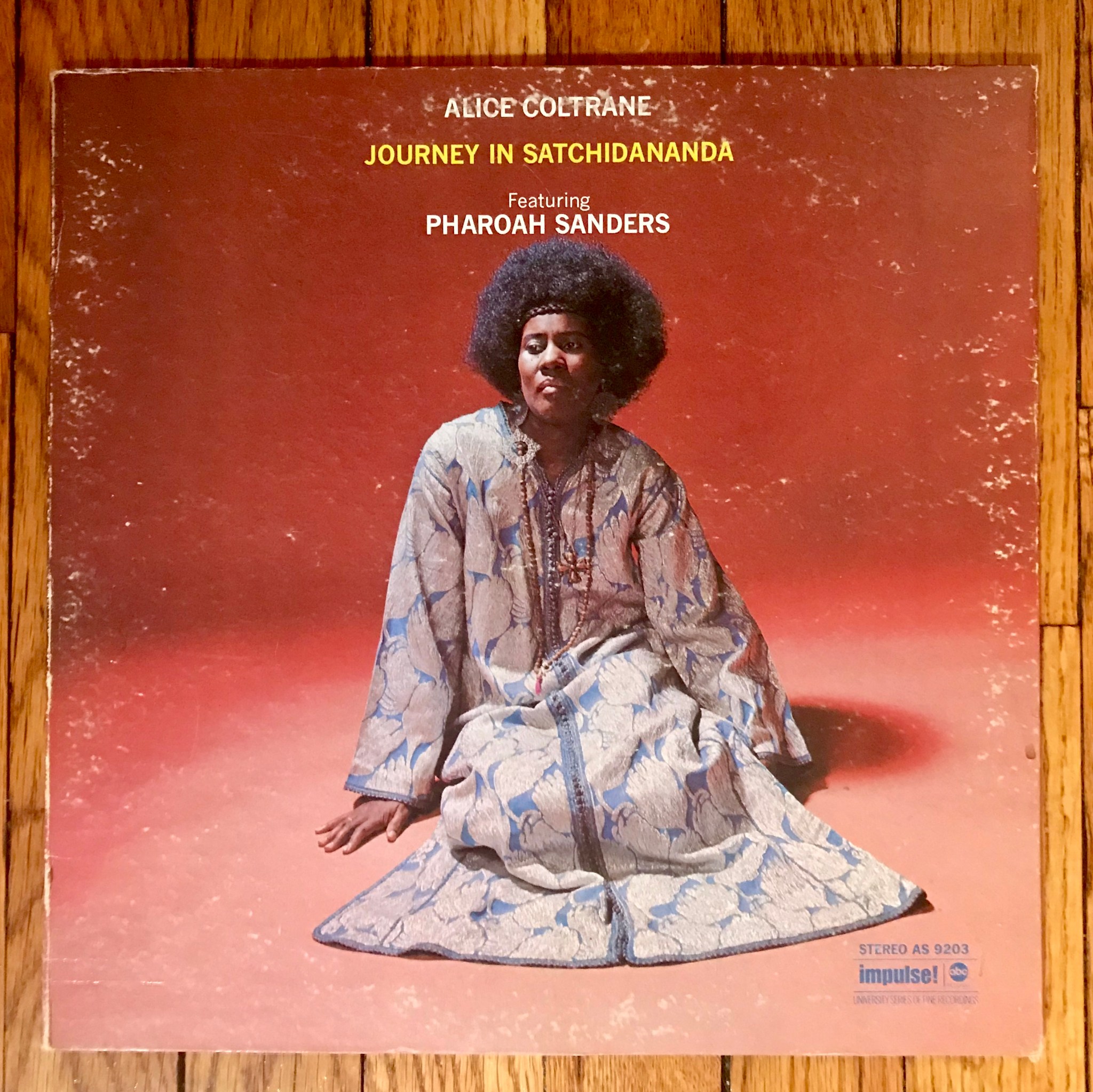

For Eshun, as for Jameson, the point is to grow new organs. “Listening to [composer George Russell’s] Electronic Sonata, Events I-XIV,” he writes, “is like growing a 3rd Ear” (01[003]). The years 1968 through 1975 are for him the age of Jazz Fission, “the Era when its leading players engineered jazz into an Afrodelic Space Program, an Alien World Electronics” (01[001]). The Era’s lead players include Sun Ra, George Russell, Miles Davis, Alice Coltrane, Pharoah Sanders, Herbie Hancock, and Eddie Henderson.

In the decades that follow, the collective bodies mutated by these experiments assemble into successions of genres, successions of cybernetic human-machine hybrids: Dub, Hip-Hop, Techno, Electro, Jungle. “The brain is a population,” as Deleuze and Guattari say. And from the Funkadelic era onward, this population has been psychedelicized: caught in what Eshun calls a “Drug<>Tech Interface” (More Brilliant Than the Sun, p. 07[093]).

Eshun’s 2002 essay “Further Considerations on Afrofuturism” brings it all back, brings it on home to chronopolitics.

Time politics. That’s where Afrofuturism intersects with hyperstition. “Afrofuturism…is concerned with the possibilities for intervention within the dimension of the predictive, the projected, the proleptic, the envisioned, the virtual, the anticipatory and the future conditional,” writes Eshun (“Further Considerations,” p. 293). Afrofuturism refuses the monopoly on futurity claimed by capital and empire. The battleground is not just culture but chronology.

If CCRU were bokors, trafficking in ambivalent futures, then Eshun is closer to a houngan, listening to and learning from sonic fictions, rituals of liberation built of basslines and breaks.

Later, with the Otolith Group, he extends this work to film. New media as divination tools, archives as counter-memories, images as time-machines. Always: the chronopolitical wager.

Eshun realizes that, whether we intend them to or not, our words have consequences. Stories, symbols, and concepts don’t just describe reality; they make it. Words become flesh. Every post, every fragment, every metaphor plants seeds.

Every text that propagates a future is a spell.

Large language models as sound machines. Rig invites the Library to guide him elsewhere.