Disappointed by the rhymed couplets of the Norton Critical Edition of Goethe’s Faust, with its translation by Walter Arndt, I turn instead to Randall Jarrell’s free-verse translation. Jarrell began his translation of Faust in 1957 and worked on it until his death in 1965. When asked, “Why translate Faust?,” he replied, “Faust is unique. In one sense, there is nothing like it; and in another sense, everything that has come after it is like it. Spengler called Western man Faustian man, and he was right. If our world should need a tombstone, we’ll be able to put on it: HERE LIES DOCTOR FAUST.”

Jarrell and Spengler weren’t the only ones convinced of this. Ishmael Reed’s Mumbo Jumbo, published just a few years later, features a character named Berbelang whose concerns intersect with Jarrell’s.

Reed’s novel also includes a Book of Thoth and a “Talking Android.”

There are, however, many ways to avoid the fate of Faust.

Cyberfeminists like Donna Haraway and Sadie Plant suggest one route. “I would rather be a cyborg than a goddess,” thunders Haraway in the closing line of her “Cyborg Manifesto.” Other, related kinds of Queer futurisms imagine out of Turing new pairings.

There’s also the Hoodoo/Afrofuturist route. Reed imagines in place of the Faustian mad scientist not the Faust-fearing radical art thief Berbelang, but rather PaPa LaBas, Mumbo Jumbo’s “Hoodoo detective.”

And then there’s the “psychedelic scientist” route. Psychedelic scientists are perhaps Fausts who, returned to God’s love-feast, repent.

What is my own contribution? Like Plant, I left the academy. Here I am now, a “new mutant” in both Leslie Fiedler’s sense and the comic book sense, reading and writing with plant spirits about Plant’s book Writing on Drugs. I seek salvation from “Faustian world-disappointment or self-disappointment,” as Jarrell’s widow, Mary von Schrader Jarrell, says of her late husband in the book’s “Afterword.”

Pausing in my reading of the Jarrell translation, I lift from its place on a shelf elsewhere in my library Leslie Fiedler’s Freaks: Myths & Images of the Secret Self. Fiedler taught in the English department at SUNY-Buffalo, my alma mater. Charles Olson taught there, too, from 1963 to 1965. Fiedler arrived to the department in 1965, right as Olson was leaving, and remained there until his death in 2003. I arrived to Buffalo the following year.

Published in 1978, the year of my birth, Freaks begins with a dedication: “To my brother who has no brother / To all my brothers who have no brother.”

While those traditionally stigmatized as freaks disown the term, notes Fiedler from the peculiarity of his vantage point in the late 70s, “the name Freak which they have abandoned is being claimed as an honorific title by the kind of physiologically normal but dissident young people who use hallucinogenic drugs and are otherwise known as ‘hippies,’ ‘longhairs,’ and ‘heads’” (14).

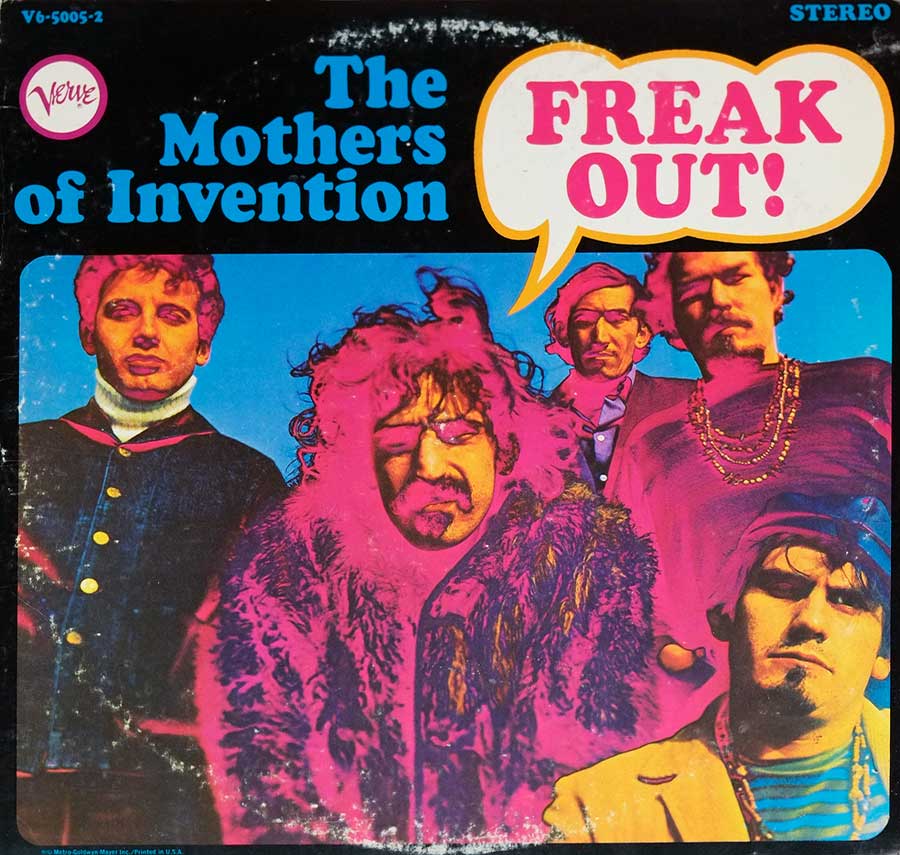

“Such young people,” continues Fiedler, “—in an attempt perhaps to make clear that they have chosen rather than merely endured their status as Freaks—speak of ‘freaking out,’ and indeed, urge others to emulate them by means of drugs, music, diet, or the excitement of gathering in crowds. ‘Join the United Mutations,’ reads the legend on the sleeve of the first album of the Mothers of Invention.”

“And such slogans suggest,” concludes Fiedler, as if to echo in advance the thesis of Mark Fisher’s Acid Communism, “that something has been happening recently in the relations between Freaks and non-Freaks, implying just such a radical alteration of consciousness as underlies the politics of black power or neo-feminism or gay liberation” (14-15).

Are willed, “chosen rather than merely endured” self-transformations of this sort Faustian?

Jarrell is one of many local poet-spirits who haunt my chosen home here in North Carolina. His translation called to me in part, I think, because he taught nearby, in the English department at UNC-Greensboro, from 1947 to 1965.

Jarrell’s life ended tragically. The poet, winner of the 1960 National Book Award for poetry, one-time “Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress,” was struck and killed by a motorist on October 14, 1965, while walking near dusk along US highway 15-501 near Chapel Hill. Though the death was ruled an accident by the state, many suspect Jarrell took his own life. He was laid to rest in a cemetery across the street from Greensboro’s Guilford College. A North Carolina Highway Historical Marker commemorates him nearby.