With its large, curtain-less, floor-to-ceiling window facing out onto a public street, my meditation room is a place of display, equal part studio and stage, wherein I perform and exhibit my daily being for others. It is in that sense much like these trance-scripts, which I imagine, by the way, to be a kind of Acid Communist variant upon the Prison Notebooks, the mind partaking in consciousness-raising and revolution while the body sits in a box. I know, of course, the absurdity of that comparison. I, for instance, lack accomplishment in any memorable, “world-historical” sense, unlike Gramsci, who headed the Italian Communist Party. My life unfolds in the long American slumber at the end of history, whereas the final years of Gramsci’s unfolded in one of Mussolini’s prisons. Did he, while “doing time,” as they say, ever abscond from the office of public intellectual? I hope he did. I hope he allowed his thoughts to dwell now and then upon the Self as consciousness and condition. Perhaps not, though. Perhaps he refused himself the luxury of “mere subjectivism,” as some of us might say—perhaps even “on principle,” as a “man of science,” his writing free of all trace of the personal. The moments I most admire in the Western Marxist tradition, however, are precisely the opposite: those “trip reports,” those brief phenomenologies of individual everyday being that we find, say, in Fredric Jameson’s report of his encounter with the Bonaventure Hotel in the famous “Postmodernism” essay, or in the confessional poetry in all but name of certain post-WWII French intellectuals like Sartre and Lefebvre. Devising a theory of Acid Communism will require a reappraisal not just of Gramsci and these others, but also of the so-called “Lacanian” turn, the late-60/early-70s moment of Althusserian Marxism in Europe and the UK, with its self-espoused anti-humanism and all of its other insights and peculiarities—all of this re-envisioned, basically, in light of the ideas and practices of humanistic and transpersonal psychologists like Abraham Maslow and Stanislav Grof. Because today’s heads, after all, exist amid vastly different circumstances. Why look for answers in so distant and so marginal a past? By the time Jameson was writing the “Postmodernism” essay for New Left Review in the 1980s, revolutionaries in the US operated largely in isolation, affiliated in many cases with academic institutions, but no longer able to identify with the consciousness of a party. Where does that leave us today, those of us sitting at our windows, wishing to act up as an oppressed class? How does the singular monadic debtor household in post-Occupy USA (by which I mean “me,” the first-person author-function, the Subject of these trance-scripts) live intentionally? How else but by the yoga of writing and zazen—sitting through, enduring, persevering, so as to instigate change both in one’s own life-world and in the life-worlds of others.

Tuesday December 11, 2018

The stories we read and tell one another compose us collectively into an intersubjective multiverse linked by each consciousness holding up to the Other its mirror. Philip K. Dick’s A Scanner Darkly is a hard novel to end a course on, hard because it contains so many prior horizons of psychedelic-utopian possibility in the uncertainty and despair of its narrative universe. I worry that the book inspires in its readers an excess of aversion to chemical modification of consciousness. The book is too unqualified in its denunciation of drug use; the book’s fictional Substance-D operates allegorically (most vividly via its street name “slow death”) as an emblem, a universal shorthand for every drug — drugs in general. Dick leaves readers without a positive alternative to the “straight” world’s miserly, hypocritical relationship to mental health, where “sanity” equals mind-numbing adherence to pre-established norms, and all are expected to board what Margo Guryan called “The 8:17 Northbound Success Merry-Go-Round.”

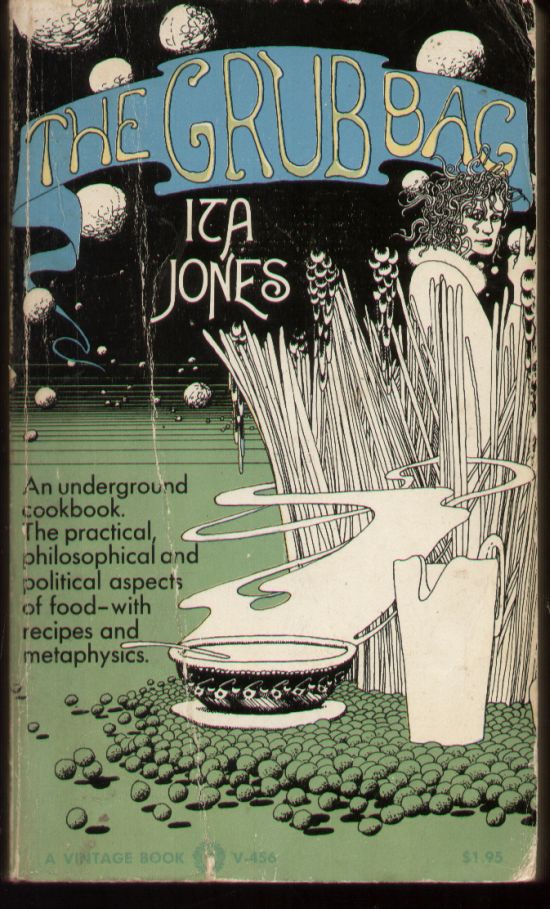

I prefer to focus instead on collecting recipes for a cookbook. The cookbook was a great utopian art form of the late 1960s and 1970s, from The Grub Bag and The Tassajara Bread Book to Ant Farm’s INFLATOCOOKBOOK of 1971. To my cookbook I add a recipe for “Vegan Cream of Mushroom and Wild Rice Soup” from the Food 52 website.

Monday December 10, 2018

As a lifetime shirker of responsibility for cooking as a necessary component of household labor, the human potential in me for communist love and compassion demands revolution, demands I spend my daily material labor-hours differently. Perhaps in so doing I can model a better mode of being. Toward that end I pull out and peruse Ita Jones’s hippie-modernist “underground cookbook,” The Grub Bag. Brad Johannsen’s other-dimensional cover art is super trippy. (For those seeking more of Johannsen’s artwork, look for copies of his book Occupied Spaces.) Jones writes to today’s reader here in the twenty-first century as if a being from a utopian future, despite The Grub Bag‘s publication almost half a century ago in March 1971. Comrades, this is the book we ought to be reading in our study groups and revolutionary sanghas. The book began as “a food column carried by the Liberation News Service,” the news service of the Movement here in the United States in the late 1960s. Jones gives us her peace brother / peace sister salute by proclaiming on the book’s back cover, “I have always been on the side of revolution, on the side of people struggling to break the chains that oppress them. I support wars of liberation. I am a mystic. I seek to penetrate the nature of nature. I am a poet. I seek meaning. I am part of a generation that exploded six years ago and my creative energy is part of that explosion.”

Sunday December 9, 2018

Consciousness needn’t commit itself to the ontological confines of Western techno-scientific rationality. The artist is one who opens portals onto other realms. Now is the time for another Dionysian awakening — for we live in an historical moment not of reason in chains but of reason unbound — automated, loosed of will — and thus free to enchain its makers. This is my problem with Michael Pollan. He wants to contain the psychedelic revolution. While acknowledging the “ungovernable Dionysian force” of drugs like acid — their effect, in other words, of “dissolving almost everything with which [they] come into contact, beginning with the hierarchies of the mind (the superego, ego, and unconscious) and going on from there to society’s various structures of authority and then to lines of every imaginable kind: between patient and therapist, research and recreation, sickness and health, self and other, subject and object, the spiritual and the material” — Pollan immediately tries to instrumentalize all of this. LSD is for him a tool to be used according to preestablished legal and technocratic protocols within a “sturdy social container” (How to Change Your Mind, pp. 214-215). There need to be rules and rituals, he says, which makes me wonder: must we accede to this alleged need, those of us hoping to build Acid Communism? Or can each one teach one — each head its own authority, its own shaman or guide?

Saturday December 8, 2018

Tune in to White Noise’s hippie modernist masterpiece, An Electric Storm, an album of utterly distinctive and sometimes deeply creepy recordings from 1969.

Pitchfork refers to the album’s “widescale psychedelic mayhem,” and that sounds about right. An Electric Storm originated from a unit of composers and engineers at BBC’s Radiophonic Workshop (best known for the theme music to Doctor Who). Julian Cope’s review of the record is so frightening, I never even made it to side two. Busied myself instead with Cope’s website Head Heritage, part of which he describes as “a Gnostic Odyssey through lost and forgotten freakouts.” The Roman emperor Julian, remember, was raised as a Christian, but after studying Neoplatonism apostatized and attempted to revive paganism. He wrote a polemic in Greek titled Against the Galileans, but the text was anathematized by subsequent rulers and lost to history, its arguments known only second-hand through work that sought to refute it. Perhaps Cope is some sort of rock ‘n’ roll re-embodiment of the Julian Ur-spirit dredged from the collective Id.

Friday December 7, 2018

From early adolescence onward, I’ve been haunted, conflicted, attracted into near identity with yet simultaneously repulsed by the wizard archetype, particularly as embodied by “Raistlin Majere,” a character introduced to me through the fantasy novels of Margaret Weis and Tracy Hickman’s Dragonlance series. Raistlin has become synonymous in my imagination with the Lucifer character in Milton — though I encountered Raistlin first. I often hear myself wondering in a ponderous, psychoanalytic way, “Why did these books grasp hold of me? What was the nature of their appeal? What was it that I heard calling to me? How did these books reconstitute and reshape me? I found in them an entire cosmology, did I not? Was it my first, my original — or was there another, one prior? Did I ever reflect self-consciously about Christianity, accept it or choose it as my mythos, know myself to believe in it — or was it only ever a series of meaningless, inexplicable rituals imposed upon me by alien authority structures: family, church, community?” Part of me has come to view Weis and Hickman as corporate corruptors of the fantastic imagination. These were books that fed and perhaps irritated, worsened, fed and prolonged my sensitivity to the violence of being labelled a “nerd” by my classmates at school. That’s a powerful memory: one’s slightly larger male classmates narrowing their eyes, clenching their fists and snarling disgustedly, “Nerd!” I remember resolving to read the Bible in its entirety and getting distracted, setting it aside, reading Tolkein, Weis and Hickman’s Dragonlance and Darksword trilogies, Marvel superhero comics, horror novelists like Clive Barker and Stephen King. From their cover art onward, the Dragonlance books are all about a universe become filled with pubescent menace: men with swords, dragon-riding women. A world ensorcelled by hormones, symbol-systems, RPGs, and media. Readers are encouraged to see themselves in the Raistlin character: a figure of great intelligence trapped in a weak and sickly body, and for that reason contemptuous of others. That contempt is localized in the figure of Raistlin’s twin brother Caramon, the sibling who inherited the pair’s physical strength. Public school attempted to divide me from this through memorization of the alternative rituals of “science” and “mathematics” — but these had none of the same seductive powers, none of the erotic charge, the pleasure felt when under the spell of a fantasy.

Thursday December 6, 2018

In fleshing out the prehistory of what Mark Fisher was calling “Acid Communism,” one’s research will eventually lead to the western Canadian province of Saskatchewan. It was at the Saskatchewan Mental Hospital in Weyburn that psychiatrists Humphry Osmond and Abram Hoffer established what Michael Pollan refers to as “the world’s most important hub” for the first wave of research into psychedelics (How to Change the World, p. 147). Osmond was lured there from England by the province’s leftist government, which beginning in the mid-1940s, as Pollan notes, “instituted several radical reforms in public policy, including [Canada’s] first system of publicly funded health care” (147).

Wednesday December 5, 2018

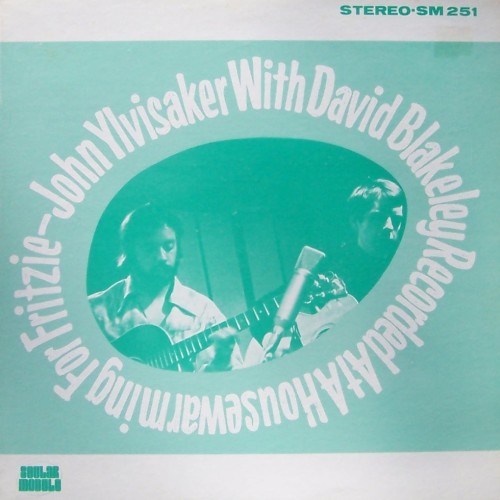

The etymology of “gonzo” unlocks a new level in my understanding of countercultural history. To celebrate, I sing along to the “Moratorium” chorus from John Ylvisaker and David Blakeley’s Recorded at a Housewarming for Fritzie, a rare private-press christian psych-folk LP released in 1972 on Soular Module.

Ylvisaker’s obituary refers to him as the “Bob Dylan of Lutheranism.” Reawakened by its use as slang among beats and hippies and entered into print to name Hunter S. Thompson’s drug-fueled brand of New Journalism, “gonzo” probably derives from the Italian figure of the simpleton or fool, the great lightener of moods who speaks cheerfully of the miracle of reconciliation. Also a play on “gone,” as in “out there,” wild and crazy, mind unfurling in the midst of a great trip. My courses are basically guided tours of elaborate, personally crafted memory palaces, demonstrations of compatibility among multiple systems of gnosis, literary, philosophical, cultural, and political texts woven into a vast assemblage, my eyes like those of the Muppet conveying moment by moment a “zany, bombastic appreciation for life.”

Tuesday November 27, 2018

I’ll be revisiting old friendships this weekend — high school friends, some of whom I haven’t seen or spoken to in decades. How might I best characterize myself for them? By what terms might I achieve peace with these brethren, unburdened of unspoken rivalries? In the past, I may have been wounded and wronged by these friends, just as I may have wounded and wronged them in return. Yet as Laura Archera Huxley counsels in her book You Are Not The Target, “each one of us has a function to fulfill. It is when we spend our time and energy looking down in contempt or looking up with sterile longing that we lose sight of this function. Envy is comparison. He who is in the continuous process of being and becoming what he really is, directs his attention to real values, not to measuring other people’s achievements” (240). What I’m suffering is what Ralph McTell calls the “Zimmerman Blues.”

I traveled far from home, lost touch, saddled myself with unrepayable debt — but amid this impoverished wandering, I followed my heart, I found my partner, I learned how to love. Freedom outside in the sun of the prison yard. The country is not one where each person owns or gets enough on which to live. The fault for that lies with the country, not me. Were it otherwise, each could attend to the beauty and the glory of the earth. In the meantime, I break away as much as I can from “compulsions, ambitions, hates, vanities, envies”; I try to conduct myself day by day as a whole being.

Monday November 26, 2018

For the artist, the universe remains a plaything, a site for open exploratory stars-in-eyes investigation. One wanders about or thumbs through books of symbols asking, “Where in the world is my next sacred-ecstatic encounter? What material should I alter, and by what process?” Curiosity leads to discovery, and discovery leads to artistic creation or invention, as in Fanita English’s transactional analysis script matrix, “Sleepy, Spunky, and Spooky,” an essay referenced in Philip K. Dick’s A Scanner Darkly.