Here I am, in another of these present-tense happenings and becomings. In this one, I become a godfather — or, more accurately, Sarah and I become godparents. The tale involves a bounce house, a ceremony, a gathering with family and relatives beside a canal. I go around doing what is asked of me for the sake of loved ones. Moments of sitting and listening bring no peace. Dipping back into Toni Morrison’s Paradise, I come upon the phrase “people lost in a blizzard” (272). Curtains covered with anchors is more how I’ve felt of late. Blue anchors, white background, pink trim. Morrison’s novel features a midwife named Lone who believes God communicates through signs to those who don’t play blind. “Playing blind,” writes Morrison, “was to avoid the language God spoke in. He did not thunder instructions or whisper messages into ears. Oh, no. He was a liberating God. A teacher who taught you how to learn, how to see for yourself. His signs were clear, abundantly so, if you stopped steeping in vanity’s sour juice and paid attention to His world” (273).

Tag: Books

Having a Coke With You

Inspired by José Esteban Muñoz’s reading of Frank O’Hara’s poem “Having a Coke With You,” I decide to include O’Hara’s Collected Poems in a bag of books that I carry north with me on my trip to New York. O’Hara is, after all, a defining figure of the New York School. His is a poetry of parties, acts, and encounters. A friend writes about him in her book. Words of hers capture my thoughts for a moment — nay, linger still, all these hours later, here in the future, among what has become of the words of he who is lost in the story. I imagine again the characters in the O’Hara poem, “drifting back and forth / between each other like a tree breathing through its spectacles.” If one’s attention is not to hold and be held by such things, one must actively turn away.

Into the Woods

Sarah suggests I camp alone for a few days in a state park while she and Frankie visit with family up north. This would be the third week of July. Some time to myself. Time to go off into the woods. It could be an adventure, assuming I plan it right. To prepare, I read Visionary Love: A Spirit Book of Gay Mythology and Trans-Mutational Faerie.

Hopework

So thinketh one of our time travelers. The one who relives the past. Let there also be a traveler who seeks and conceives here in the dailiness of his lived experience a utopian future. As Joshua Chambers-Letson, Tavia Nyong’o, and Ann Pellegrini note in their foreword to the 10th Anniversary Edition of José Esteban Muñoz’s Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity, “Hope is work; we are disappointed; what’s more, we repeatedly disappoint each other. But the crossing out of ‘this hoping’ is neither the cancellation of grounds for hope, nor a discharge of the responsibility to work to change present reality. It is rather a call to describe the obstacle without being undone by that very effort” (x). The obstacle is a challenge we must both survive and surpass, Muñoz argues, “to achieve hope in the face of an often heart breaking reality.”

Monday June 28, 2021

Friends, let us hold space and remember Cruel Optimism author Lauren Berlant upon word of their passing. “A relation of cruel optimism exists,” Berlant wrote, “when something you desire is actually an obstacle to your flourishing” (1). We are all in such relationships, are we not? “Speaking of grieving,” they wrote, it was in grieving French philosopher Jean-François Lyotard that Berlant “first saw optimism as the thing that keeps the event open, for better or ill” (viii). How does one come to recognize that one’s optimisms have become “cruel”? What is it that moves us out of ourselves? “A satisfying something,” they whisper. “An intelligence beyond rational calculation” (2). And we are here, we are caught in this “scene of fantasy,” we are in the throes of it. ‘Tis our present, our contemporary moment. And this moment is what Berlant calls an “impasse”: “a time of dithering from which someone or some situation cannot move forward” (4). That is the genre of these trance-scripts, is it not? “The impasse is a stretch of time in which one moves around with a sense that the world is at once intensely present and enigmatic, such that the activity of living demands both a wandering absorptive awareness and a hypervigilance that collects material that might help to clarify things” (4).

Friday June 25, 2021

I’m about half a year behind in posting these trance-scripts. Arriving to summer solstice, I post trance-scripts about winter. I type up New Year’s Day as I sit in summer sun. And as I do so, the idea dawns upon me: I can edit. I can revise. Trance-scripts could become a time-travel narrative. Through the eerie psychedelic echo and delay of the trance-script, I can affect-effect the past. I’ve done this already in minor ways, adjusting a word or two here and there. Time travel is such a modernist conceit, though, is it not? It’s modernist when conceived as a power wielded by a scientist or some sort of Western rationalist subject, as in H.G. Wells’s genre-defining 1895 novel The Time Machine. But in fact, much of the genre troubles the agency of the traveler. Think of Marty McFly, forced to drive Doc Brown’s Delorean while fleeing a van of rocket-launcher-armed Libyan assassins in Back to the Future. Or think of Dana, the black female narrator-protagonist in Octavia E. Butler’s novel Kindred. For Dana, travel is a forced migration to the time and place of an ancestor’s enslavement. One moment, she’s in 1970s Los Angeles; the next moment, she’s trapped on a plantation in pre-Civil War Maryland. Be that as it may, there is still the matter of these trance-scripts. It all seems rather complicated, this idea of tinkering with texts post facto. Yet here I am doing it: editing as I write. What, then, of this mad-professorly talk of “time-travel”? What would change, under what circumstances, and why? Let us be brave in our fantasies, brave in our imaginings.

Thursday June 24, 2021

What are we talking about when we talk about “political theology”? It’s a rejection of the secularization thesis. Religion never goes away; theological notions haunt the structures and discourses of capitalist modernity. I think of the lyrics to Buffy Sainte-Marie’s song “God Is Alive, Magic Is Afoot.” The song’s title is a line from a poem in Leonard Cohen’s 1966 novel Beautiful Losers. “I propped two pages of his book up on a music stand,” she recalled when asked about the song in an interview, “and I just sang it out, ad-libbing the melody and guitar music together as I went along.” Who is it that tells us “mind itself is magic coursing through the flesh / And flesh itself is magic dancing on a clock / And time itself, the magic length of God”? Is it Sainte-Marie, or is it Catherine Tekakwitha, the 17th century Mohawk saint worshipped by the narrator of Cohen’s novel?

Tuesday June 22, 2021

Let this book of ours be a joyous one. Let the writing of it happen in the manner of a dance song or dream. Find in it an occasion to read Gurney Norman’s Divine Right’s Trip, a “novel of the counterculture” serialized in (and thus functioning as a paratext to) The Last Whole Earth Catalog. Leary, Di Prima, Huxley, Olson, Ginsberg, Kesey, Baraka, Sanders: all have their places, all have their roles in this tale we are about to tell. Words written on behalf of Utopia. ‘Twas a time when the not-yet was still possible, and that time is now.

Monday June 21, 2021

“Put a lemon on it” is the first of several words received as I sit eyes closed beside a pool. Words overheard, duly noted, to be reimagined in the evening hours as dream material and as a step in a recipe for pasta with broccoli. There has been a desire of late, some chakra lighting up all that is. I play it records, feed it the exalted public speech of Odetta at Carnegie Hall.

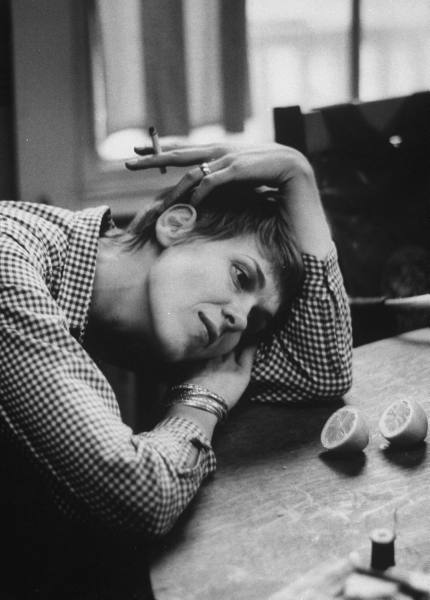

A kind of love is organizing all things, Amens everywhere “all over this land.” That’s what Leary thought, isn’t it? “The history of our research on the psychedelic experience,” he writes, “is the story of how we learned how to pray” (High Priest, p. 171). Let us include among the characters in this story IFIF medical director Madison Presnell. A photograph of Presnell appears in the April 16, 1963 issue of Life magazine. A photographer with the magazine accompanies Cambridge, MA housewife Barbara Dunlap on her first acid trip. Presnell administers the drug. The caption for the final photograph in the series reads, “Dunlap smokes a cigarette while seeing visions in the seeds of a lemon.”

Sunday June 20, 2021

Indigenous ways of knowing; Black Radical thought; Surrealism; Afrofuturism; Zen Buddhism. All have been guides: blueprints for counter-education for those who wish to be healed of imperial imposition. All provide maps of states other than the dominant capitalist-realist one. Hermann Hesse describes one such line of flight in his short novel The Journey to the East, a book first published in German in 1932, unavailable in English until 1956. Timothy Leary’s League for Spiritual Discovery takes after the League in Hesse’s novel. It, too, is but a part of a “procession of believers and disciples” moving “always and incessantly…towards the East, towards the Home of Light” (Hesse 12-13). Two of Leary’s psychedelic utopias, in other words, take their names from books by Hesse: both the League for Spiritual Discovery and its immediate precursor, the Castalia Foundation.