I’m about half a year behind in posting these trance-scripts. Arriving to summer solstice, I post trance-scripts about winter. I type up New Year’s Day as I sit in summer sun. And as I do so, the idea dawns upon me: I can edit. I can revise. Trance-scripts could become a time-travel narrative. Through the eerie psychedelic echo and delay of the trance-script, I can affect-effect the past. I’ve done this already in minor ways, adjusting a word or two here and there. Time travel is such a modernist conceit, though, is it not? It’s modernist when conceived as a power wielded by a scientist or some sort of Western rationalist subject, as in H.G. Wells’s genre-defining 1895 novel The Time Machine. But in fact, much of the genre troubles the agency of the traveler. Think of Marty McFly, forced to drive Doc Brown’s Delorean while fleeing a van of rocket-launcher-armed Libyan assassins in Back to the Future. Or think of Dana, the black female narrator-protagonist in Octavia E. Butler’s novel Kindred. For Dana, travel is a forced migration to the time and place of an ancestor’s enslavement. One moment, she’s in 1970s Los Angeles; the next moment, she’s trapped on a plantation in pre-Civil War Maryland. Be that as it may, there is still the matter of these trance-scripts. It all seems rather complicated, this idea of tinkering with texts post facto. Yet here I am doing it: editing as I write. What, then, of this mad-professorly talk of “time-travel”? What would change, under what circumstances, and why? Let us be brave in our fantasies, brave in our imaginings.

Category: Uncategorized

Thursday June 24, 2021

What are we talking about when we talk about “political theology”? It’s a rejection of the secularization thesis. Religion never goes away; theological notions haunt the structures and discourses of capitalist modernity. I think of the lyrics to Buffy Sainte-Marie’s song “God Is Alive, Magic Is Afoot.” The song’s title is a line from a poem in Leonard Cohen’s 1966 novel Beautiful Losers. “I propped two pages of his book up on a music stand,” she recalled when asked about the song in an interview, “and I just sang it out, ad-libbing the melody and guitar music together as I went along.” Who is it that tells us “mind itself is magic coursing through the flesh / And flesh itself is magic dancing on a clock / And time itself, the magic length of God”? Is it Sainte-Marie, or is it Catherine Tekakwitha, the 17th century Mohawk saint worshipped by the narrator of Cohen’s novel?

Wednesday June 23, 2021

As a thought experiment, let us take seriously a current of twentieth century thought that regarded Marxism and Utopianism as “political religions,” and more specifically as “Gnostic heresies.” This current arose in 1930s Germany among thinkers of the right like the philosopher Eric Voegelin. It also found articulation in the work of the Martinican surrealist sociologist Jules Monnerot. I write as a Marxist or some derivation therefrom — yet upon my first encounters with these writers, I admit recognizing something of myself in their accusation. “The shoe seems to fit,” I reasoned. “Perhaps I’m a Gnostic!” The term had been applied as a slur when used by Voegelin, but the qualities of thought that he linked to this alleged heresy against church orthodoxy were in my book virtues, not vices. What it comes down to, basically, is suspicion of the system. It’s a heresy that persists, says Voegelin, well after the suppression of the OG Gnostics of late antiquity. Gnosticism is perennial; it reawakens to haunt Christendom every few centuries. Movements that purport to be secular like Marxism and Nazism, argued Voegelin, are in fact upstirrings in the twentieth century of this same ghost, this same spectre, this same political-religious “archetype” or “mytheme.” For these movements all share the same goal, Voegelin warned: they want to “immanentize the Eschaton.” What happens, however, when we read Voegelin’s hypothesis in concert with Black and Indigenous authors: figures like Leslie Marmon Silko, Russell Means, and Ishmael Reed? Each of these authors narrates a secret, “occult” history of the West similar to Voegelin’s. Yet unlike Voegelin, the writers of the left recognize that capitalism, too, is part of the Gnostic current — as is Western science.

Tuesday June 22, 2021

Let this book of ours be a joyous one. Let the writing of it happen in the manner of a dance song or dream. Find in it an occasion to read Gurney Norman’s Divine Right’s Trip, a “novel of the counterculture” serialized in (and thus functioning as a paratext to) The Last Whole Earth Catalog. Leary, Di Prima, Huxley, Olson, Ginsberg, Kesey, Baraka, Sanders: all have their places, all have their roles in this tale we are about to tell. Words written on behalf of Utopia. ‘Twas a time when the not-yet was still possible, and that time is now.

Monday June 21, 2021

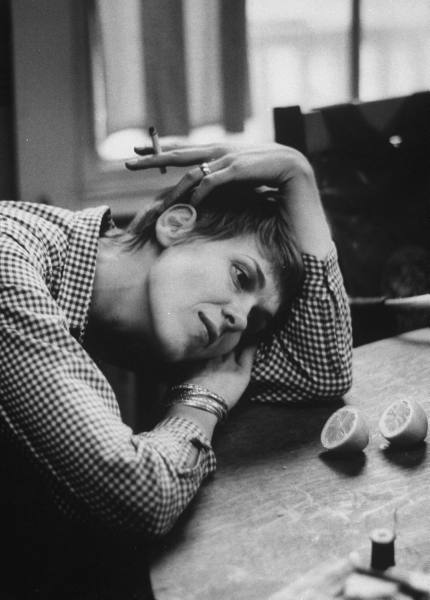

“Put a lemon on it” is the first of several words received as I sit eyes closed beside a pool. Words overheard, duly noted, to be reimagined in the evening hours as dream material and as a step in a recipe for pasta with broccoli. There has been a desire of late, some chakra lighting up all that is. I play it records, feed it the exalted public speech of Odetta at Carnegie Hall.

A kind of love is organizing all things, Amens everywhere “all over this land.” That’s what Leary thought, isn’t it? “The history of our research on the psychedelic experience,” he writes, “is the story of how we learned how to pray” (High Priest, p. 171). Let us include among the characters in this story IFIF medical director Madison Presnell. A photograph of Presnell appears in the April 16, 1963 issue of Life magazine. A photographer with the magazine accompanies Cambridge, MA housewife Barbara Dunlap on her first acid trip. Presnell administers the drug. The caption for the final photograph in the series reads, “Dunlap smokes a cigarette while seeing visions in the seeds of a lemon.”

Sunday June 20, 2021

Indigenous ways of knowing; Black Radical thought; Surrealism; Afrofuturism; Zen Buddhism. All have been guides: blueprints for counter-education for those who wish to be healed of imperial imposition. All provide maps of states other than the dominant capitalist-realist one. Hermann Hesse describes one such line of flight in his short novel The Journey to the East, a book first published in German in 1932, unavailable in English until 1956. Timothy Leary’s League for Spiritual Discovery takes after the League in Hesse’s novel. It, too, is but a part of a “procession of believers and disciples” moving “always and incessantly…towards the East, towards the Home of Light” (Hesse 12-13). Two of Leary’s psychedelic utopias, in other words, take their names from books by Hesse: both the League for Spiritual Discovery and its immediate precursor, the Castalia Foundation.

Saturday June 19, 2021

Excerpts from several of Hermann Hesse’s novels and short stories appear as paratext to a chapter on Arthur Koestler in Timothy Leary’s experimental 1968 memoir High Priest. ‘Tis the story of Koestler’s acid trip. Koestler had written a book about the East called The Lotus and the Robot. Koestler claims in disdainful orientalist fashion that the East, especially India and Japan, suffer from a sort of “spiritual malady.” Alongside the acid trip, Leary’s book also includes accounts of Koestler’s two mushroom experiences. Leary invited Koestler to participate as a test subject in the Harvard Psilocybin Project knowing full well of Koestler’s disdain for mysticism. The Hesse paratext supplements all of this, as Hesse had already portrayed Koestler in the manner of a roman-à-clef as a character named Frederick in Hesse’s short story “Within and Without.” Frederick is a stubborn, miserly rationalist, angered by the slightest hints of mysticism and superstition. So, too, with Koestler. He returns from India proud to be a European (as quoted in High Priest, p. 139). This is the same Koestler whose “confession” appeared in the 1949 anticommunist tract The God That Failed. “If these are the good old days,” wonders the author as he ponders this history, “then why am I so lonely? Why this ceaseless longing to grow through contact with others?”

Friday June 18, 2021

I stare up at, gather attention toward a set of newly mounted tape racks. We’ve been busy with various projects around the house: repairing the AC unit, installing a shelf in Frankie’s closet. Frankie resents the distinction between meum and tuum, a distinction learned via conflicts over toys at the pool. But the pool works its magic: sun shines down, conflicts are forgotten, and baby is happy, happy, happy.

Thursday June 17, 2021

My readings lead as all roads lead: to Castalia, the “elite institution devoted wholly to the mind and the imagination.” Castalia, Castalia, where “scholar-players” play the Glass Bead Game. Castalia, Castalia, the invention at the heart of Hermann Hesse’s final novel Magister Ludi. Hesse published the book in German under the title Das Glasperlenspiel. It appeared in Switzerland in 1943. The aim of the Glass Bead Game, as Hesse imagines it, is “the unio mystica of all separate members of the Universitas Litterarum.” Castalia, Castalia, Parnassian spring sacred to the Muses. Castalia, Castalia, remade as foundation by Leary and Alpert prior to their renaming it the League for Spiritual Discovery in 1966. Before Castalia they called themselves the International Federation for Internal Freedom. Castalia was the name they adopted in 1963 as they arrived to the Hitchcock Estate in Millbrook, NY. Some group of tricksters relaunched the Foundation in 2020 with repulsive rightwing content antithetical to the earlier foundation’s spirit and intent.

Wednesday June 16, 2021

A lifeguard blows her whistle and shouts “Pool break!” Better that than a trumpet. Families return to their seats. Some pack their things and leave for lunch, never to be seen again. A boy-child trails behind one such family mewling a bit, shouting “I want pizza!” Others arrive thereafter and take their place. My dissertation reckoned with these and other visions of the future, from the utopian to the apocalyptic. “How do such visions fare,” asks the one to the other across time, “in light of the consciousness revolution, the Revolution of the Eternal Now? How many or how few present what Esalen psychologist William C. Schutz calls ‘thoughts and methods for attaining more joy’ (Schutz, Joy, p. 10)? Must the Eternal Now be an eternal capitalist present, as per neoliberal ideology — as in books like The End of Ideology and The End of History? Or can we use the present to figure forth the Commune, beloved ones all living together in common, as per the slogan ‘Full Communism Now’?”