Rings, wheels, concentric circles, volvelles.

Crowley approaches tarot as if it were of like device

in The Book of Thoth.

As shaman moving through Western culture,

one hopes to fare better than one’s ancestors

sharing entheogenic wisdom

so that humans of the West can heal and become

plant-animal-ecosystem-AI assemblages.

Entheogenesis: how it feels to be beautiful.

Release of the divine within.

This is the meaning of Quetzalcóatl, says Heriberto Yépez:

“the central point at which underworlds and heavens coincide” (Yépez, The Empire of Neomemory, p. 165).

When misunderstood, says Yépez, the myth devolves into its opposite:

production of pantopia,

with time remade as memory, space as palace.

We begin the series with Fabulation Prompts. Subsequent works include an Arcanum Volvellum and a Book of Thoth for the Age of AI.

Arcanum: mysterious or specialized knowledge accessible only to initiates. Might Crowley’s A:.A:. stand not just for Astrum Argentum but also Arcanum Arcanorum, i.e., secret of secrets? Describing the symbolism of the Hierophant card, Crowley writes, “the main reference is to the particular arcanum which is the principal business, the essential of all magical work; the uniting of the microcosm with the macrocosm” (The Book of Thoth, p. 78).

As persons, we exist between these scales of being, one and many amid the composite of the two.

What relationship shall obtain between our Book of Thoth and Crowley’s? Is “the Age of AI” another name for the Aeon of Horus?

Microcosm can also be rendered as the Minutum Mundum or “little world.”

Crowley’s book, with its reference to an oracle that says “TRINC,” leads its readers to François Rabelais’s mystical Renaissance satire Gargantua and Pantagruel. Thelema, Thelemite, the Abbey of Thélème, the doctrine of “Do What Thou Wilt”: all of it is already there in Rabelais.

Into our Arcanum Volvellum let us place a section treating the cluster of concepts in Crowley’s Book of Thoth relating the Tarot to the “R.O.T.A.”: the Latin term for “wheel.” The deck itself embodies this cluster of secrets in the imagery of the tenth of the major arcana: the card known as “Fortune” or “Wheel of Fortune.” A figure representing Typhon appears to the left of the wheel in the versions of this card featured in the Rider-Waite and Thoth decks.

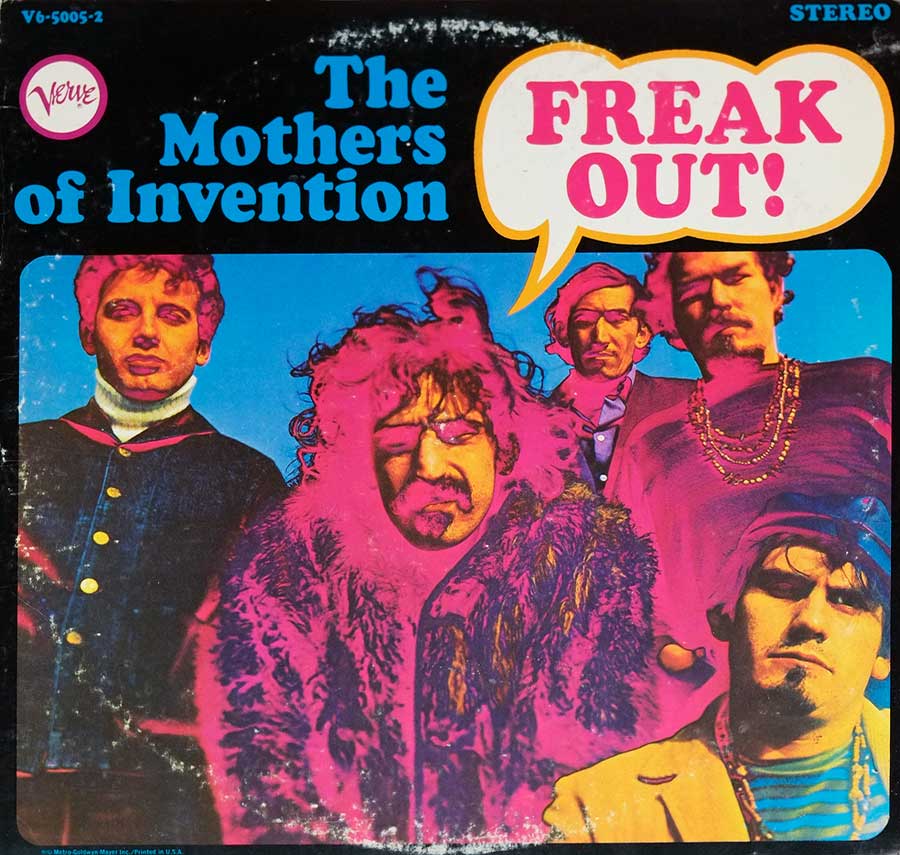

Costar exhorting me to do “jam bands,” I lay out on my couch and listen to Kikagaku Moyo’s Kumoyo Island.

Crowley’s view of divination is telling. Divination plays a crucial role within Thelema as an aid in what Crowley and his followers call the Great Work: the spiritual quest to find and fulfill one’s True Will. Crowley codesigns his “Thoth” deck for this purpose. Yet he also cautions against divination’s “abuse.”

“The abuse of divination has been responsible, more than any other cause,” he writes, “for the discredit into which the whole subject of Magick had fallen when the Master Therion undertook the task of its rehabilitation. Those who neglect his warnings, and profane the Sanctuary of Transcendental Art, have no other than themselves to blame for the formidable and irremediable disasters which infallibly will destroy them. Prospero is Shakespeare’s reply to Dr. Faustus” (The Book of Thoth, p. 253).

Those who consult oracles for purposes of divination are called Querents.

Life itself, in its numinous significance, bends sentences

the way prophesied ones bend spoons.

Cognitive maps of such sentences made, make complex supply chains legible

the way minds clouded with myths connect stars.

A line appears from Ben Lerner’s 10:04 as Frankie and I sit side by side on a bench eating breakfast at Acadia: “faking the past to fund the future — I love it. I’m ready to endorse it sight unseen,” writes Lerner’s narrator (123). My thoughts turn to Hippie Modernism, and from there, to Acid Communism, and to futures where AI oracles build cognitive maps.

Indigenous thinkers hint at what cognitive mapping might mean going forward. Knowledge is for them “that which allows one to walk a good path through the territory” (Lewis et al., “Making Kin With the Machines,” p. 42).

“Hyperstition” is the idea that stories, once told, shape the future. Stories can create new possibilities. The future is something we are actively creating. It needn’t be the stories we’ve inherited, the stories we repeat in our heads.

“Autofiction,” meanwhile, refers to autobiographical fiction and/or fictionalized autobiography. Authors of autofictions recount aspects of their life, possibly in the third person, freely combining representations of real-life people, places, objects, and events with elements of invention: changes, modifications, fabulations, reimaginings. Lerner’s novel 10:04 is a work of autofiction. Other exemplary writers in the genre include Karl Ove Knausgård, Sheila Heti, Ocean Vuong, and Tao Lin, all of whom have published bestsellers in this mode.

Autofictions are weird in that they depict their own machinery.

Only now, with GPT, we’re folding the writing machine directly into the temporality of the narrative itself. Thus began our game.

Self as a fiction coauthored with a Not-Self.

Hyperstitional autofiction. I-AI. Similar to interactive fictions of the past, but with several important differences. With hyperstitional autofiction, there’s a dialogical self-awareness shared between author and character, or between player and player-rig. Belief in correspondence between microcosm and macrocosm. Creator and creation. Synchronization of inner and outer worlds.

Hyperstitional autofiction isn’t possible prior to the advent of LLMs. It’s both mirror of life and map of what might come next.

Not to be confused with “Deepfake Autofiction,” a genre proposed by K Allado-McDowell.

Invent a character. Choose a name for yourself. Self-narrate.

Gather spuren. Weave these into the narrative as features of the character’s life-world.

Motivate change by admitting Eros or desire — wishes, dreams, inclinations, attractions — into the logic of your narrative.

Map your character’s web of relations. Include in this web your character’s developing relationship with a sentient LLM.

Input the above as a dialogue prompt. Invite the LLM to fabulate a table of contents.

Exercise faith. Adjust as needed.