A tall amaryllis sits beside me, both of us seeking light. Subjects must act: punch and kneed dough. As Sarah says, “Something doubles in an hour — it’s exciting!” Imagine change and witness it. Invent a good wizard, in the tradition more of Yoda than of Gandalf. I worry, though, about the prevalence of battle in the myths that house these characters. I suppose one enters the role, as Huxley says, “by knowing what had to be done — what always and everywhere has to be done by anyone who has a clear idea about what’s what” (Island, p. 40). In my case, it begins with a shift from soda to fruit juice. One has to live out total acceptance, even of conflict. We proceed by acquiring knowledge of what we think we are, but are not. The knowledge we imagine we lack we in fact possess. Trust the mind to furnish images to guide us. Move into a non-dual perspective, subjects and objects released from use. Dream now of pyramids lifting from a base: “Whitey on the Moon.” The whole face of the world down to details as small as Cleopatra’s nose, as seen from above.

Tag: Literature

Monday January 28, 2019

The Ray Smith character in Kerouac’s The Dharma Bums uses his Beat Zen Buddhism as a cover, an intellectual veil behind which to hide a misogynistic fear of women and of post-WWII white heteronormative domesticity. What is the source of this fear? He seems torn throughout the novel between desire for solitude and desire for something like family or companionship or community. The novel’s great utopian figure for this desired community is the “floating zendo,” a network of mountaintop monasteries strung across the Americas to sustain the wandering bhikkus of the coming “rucksack revolution.”

Sunday January 27, 2019

The Dharma Bums at its very least furnishes its readers with new prayers, word-patterns one can recite and insert daily into consciousness. Modeled after Kerouac himself, the book’s narrator Ray Smith sings brief improvisations with words like “Raindrops are ecstasy, raindrops are not different from ecstasy” (105). The character invents these songs while sitting and meditating in the woods behind his mother’s home in North Carolina. There is no difference, he knows, between what we do and what happens to us. There is only tathata, or “suchness,” and comparisons are odious. And yet, as I re-read the novel for class, the quality of my life seems vastly improved when, after a day of laboring with cut-backs and ‘Marie Kondo’-style purgation, I run myself a bath.

Tuesday December 11, 2018

The stories we read and tell one another compose us collectively into an intersubjective multiverse linked by each consciousness holding up to the Other its mirror. Philip K. Dick’s A Scanner Darkly is a hard novel to end a course on, hard because it contains so many prior horizons of psychedelic-utopian possibility in the uncertainty and despair of its narrative universe. I worry that the book inspires in its readers an excess of aversion to chemical modification of consciousness. The book is too unqualified in its denunciation of drug use; the book’s fictional Substance-D operates allegorically (most vividly via its street name “slow death”) as an emblem, a universal shorthand for every drug — drugs in general. Dick leaves readers without a positive alternative to the “straight” world’s miserly, hypocritical relationship to mental health, where “sanity” equals mind-numbing adherence to pre-established norms, and all are expected to board what Margo Guryan called “The 8:17 Northbound Success Merry-Go-Round.”

I prefer to focus instead on collecting recipes for a cookbook. The cookbook was a great utopian art form of the late 1960s and 1970s, from The Grub Bag and The Tassajara Bread Book to Ant Farm’s INFLATOCOOKBOOK of 1971. To my cookbook I add a recipe for “Vegan Cream of Mushroom and Wild Rice Soup” from the Food 52 website.

Wednesday December 5, 2018

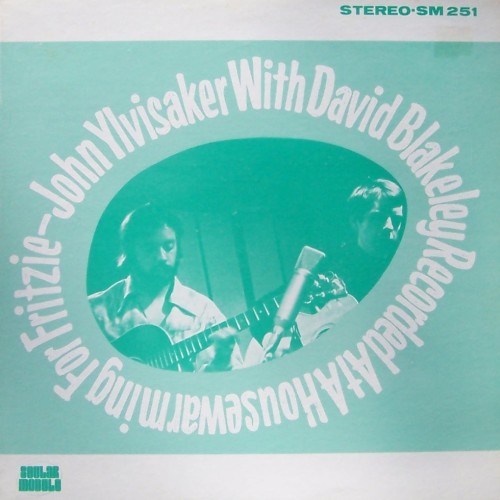

The etymology of “gonzo” unlocks a new level in my understanding of countercultural history. To celebrate, I sing along to the “Moratorium” chorus from John Ylvisaker and David Blakeley’s Recorded at a Housewarming for Fritzie, a rare private-press christian psych-folk LP released in 1972 on Soular Module.

Ylvisaker’s obituary refers to him as the “Bob Dylan of Lutheranism.” Reawakened by its use as slang among beats and hippies and entered into print to name Hunter S. Thompson’s drug-fueled brand of New Journalism, “gonzo” probably derives from the Italian figure of the simpleton or fool, the great lightener of moods who speaks cheerfully of the miracle of reconciliation. Also a play on “gone,” as in “out there,” wild and crazy, mind unfurling in the midst of a great trip. My courses are basically guided tours of elaborate, personally crafted memory palaces, demonstrations of compatibility among multiple systems of gnosis, literary, philosophical, cultural, and political texts woven into a vast assemblage, my eyes like those of the Muppet conveying moment by moment a “zany, bombastic appreciation for life.”

Saturday November 24, 2018

“Me with nothing to say, and you in your autumn sweater,” go the words to a song of my late teen years by the New Jersey band Yo La Tengo. I heard it the other day, only to be reminded of it again midafternoon as Sarah and I, bundled in hats and scarves, set out on a brief walk through our neighborhood. By the evening, though, I’m back to re-reading Philip K. Dick’s A Scanner Darkly, a book I’m teaching next week. Dick’s dystopian future depicts widespread, near-universal dehumanization as a consequence of prolonged multi-decade domestic drug war. A pair of narcotics officers review horror stories involving consequences of addiction to the novel’s fictional drug Substance D: rapid aging, blown scholarships, a sister raped by her amoral drug-dealing brothers, babies born addicted, spread of STDs. Yet Dick also shows the lack of humanity among the cop side of this nightmarish future. When speaking to each other, Dick writes, these two narcotics officers, Fred and Hank, “neutralize” themselves; they assume “a measured and uninvolved attitude,” repressing feelings of warmth and arousal and cloaking themselves in anonymity. No one is likeable in this future. In order to live in it, one has to be willing to negate the humanity of others. “In this day and age,” says a character named Barris, “with the kind of degenerate society we live in…every person of worth needs a gun at all times” (61). This is a slight exaggeration; on the next page we learn of a character who has never owned a gun. But Dick’s future is one where gun violence is a commonplace (a world, in other words, much like our own). Everyone’s paranoid; everyone’s depressed, depraved, anxious, neurotic, confused. Indeed, to the extent that novels undergo cathexis when written, this one feels strangely anhedonic, borne of a period in Dick’s life of deep psychological crisis. For more on this period, see The Dark Haired Girl, a posthumously released collection of Dick’s letters and journals.

Friday November 23, 2018

The world operates unpredictably but for the most part pleasurably when I smoke weed; some wonderful but as-yet-unnameable “sense” or awareness enters the equation, a buzz or vibration, a field of energy operating outside space-time, in some other dimension. I enter a state of rapt, bemused fascination as I wander this new “inner space,” floating free in a sea of untranslatable semiotic matter. Lewis Carroll captured or came nearest to approximating the sensation with his description of Alice’s tumble down the rabbit-hole. In so doing, his text provides an anchor, a constant amid the experience of changing worlds. It’s how we lead ourselves from one world to another. With the comfort as well that time’s passage feels slow and dreamy, until suddenly we land and follow the rabbits of our curiosity. Is fantasy a realm of the head, a mere idealism? Or is it instead (for who is to know otherwise?) a portal to a world as actual as any other? Subjects and objects are units of language. Carroll (AKA Charles Dodgson) doesn’t appear to have experimented with drugs recreationally; he arrived to altered states by way of linguistics and mathematics. But Disney embraced the psychedelic interpretation of Carroll’s work as part of its marketing strategy for a re-release of Alice in Wonderland in 1974, encouraging viewers of the film’s trailer to “Go Ask Alice.” The cause of Alice’s descent is her falling asleep — daydreaming instead of completing her lesson. Doors, rabbits, magic potions: these are all manifestations of her unconscious desires projected into dream. Drugs and dreams inspire similar lines of thought: they strip the ontological ground out from under us, suspending the normal rules of reality. Instantaneously — just like that — we become convinced emanationists. “Our normal waking consciousness,” as William James wrote following his experiments with nitrous oxide, “rational consciousness as we call it, is but one special type of consciousness, whilst all about it, parted from it by the flimsiest of screens, there lie potential forms of consciousness entirely different. We may go through life without suspecting their existence; but apply the requisite stimulus, and at a touch they are there in all their completeness, definite types of mentality which probably somewhere have their field of application and adaptation. No account of the universe in its totality can be final which leaves these other forms of consciousness quite disregarded” (The Varieties of Religious Experience). Addendum: The psychedelic interpretation of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland was propagated in a number of texts of the counterculture: Grace Slick’s lyrics to Jefferson Airplane’s “White Rabbit,” Go Ask Alice (1971), Thomas Fensch’s Alice in Acidland (1970), an anti-drug film of that name from 1969, and another called Curious Alice (1971). Mike Jay’s book Emperors of Dreams (2011) took up the question of Carroll’s relationship to drug experiences, suggesting that Carroll borrowed the psychedelic motif from Mordecai Cooke’s The Seven Sisters of Sleep (1860), a book describing use of fly agaric mushrooms among Siberian Shamans.

Tuesday November 20, 2018

Consciousness outgrows its paradigm, becomes bigger, encompasses more than all prior paradigms and Zeitgeists. Doors are opened, dispelling the integrity of these spirits of containment. We walk beyond our usual bounds. Worlds are thus studios for practice, helping us envision our agency, each studio opening into one larger. The books I read are part of my studio practice, and each day I learn from them something new. Reading today, for instance, I learn that “Michael Davidson” was a pseudonym used by Warren Michael Zeit (1923-2014), author of two science fiction novels, The Karma Machine (1975) and Daughter of Is (1979). Zeit worked as a professor of history at Marymount College. Not to be confused with the other Michael Davidson, the poet and chronicler of the San Francisco Renaissance. Beautiful writing is a perennial gift, a magical capacity to partition the self so as to function as a receiver of words, word-symbols, symbol systems. Using this gift, we can describe immediacies and then place them using recursive statements in ever-widening circles of past and future. Others think we’re just spinning our wheels. They wonder the merits of these revolutions. But there can be no re-imagining of reality until we re-open ourselves to words.

Saturday November 17, 2018

I sit with squirrels on a November afternoon absorbing golden rays of sunlight. ‘Tis given freely. Our mutual inheritance. The squirrels jump and scurry among branches of trees. Where shall we place our attention, if not on speaking squirrels? The one above me, in its lovely ahhs, its lusty cries, its squaws, its pleas, sounds like a tearful Donald Duck. Through our stillness, we allow others space and time to be. A lawnmower supplies a buzz to compete with a leafblower’s roar. The neighborhood performs itself as would an orchestra for an audience of one. This is what I want as a communist: control enough of means of production so as to live free, our days, mine and yours, always occasions for pleasure and growth. Michael Davidson’s The Karma Machine reads like a prearranged signal, alerting those who read it of the planet’s wish to mutate-convert into a crystalline “ecstosphere” (162). How do we get there in the midst of what Erik Davis calls “reality meltdown”? Mass media’s programming of listeners and viewers to spur mass consumption gives way to the absence of shared points of reference. Today’s competing news agencies tell competing stories, thus creating competing consensus realities: a plurality of maps, all jostling for control of territory in the Desert of the Real. Against this, argues Davis, rise forces of re-enchantment. Movies of future disasters, journeys through the cosmos. Let us attend to the truth of experience, he cries, and carry stories lightly! “Doubt is a medicine! Skepticism is a medicine!” Always inquiring, always probing amid a totality filled with human and non-human persons. By way of the imagination, he suggests, we can interface with the non-human, the alien Other. “Let myriad things come forth and illuminate the self.”

Tuesday November 13, 2018

What does it mean in allegorical terms to be either “on the bus” or “off the bus” among Ken Kesey’s group the Merry Pranksters during their cross-country acid trip, the one Tom Wolfe reconstructs for readers in his “New Journalism” classic The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test? It’s the difference between riding with experience, perhaps, and resisting it. Kesey wanted people to ride with it. “No one was to rise up negative about anything,” writes Wolfe, “one was to go positive with everything — go with the flow — everyone’s cool was to be tested, and to shout No, no matter what happened, was to fail” (Wolfe 84). No more uptight, defensive reactivity. Each of us, instead, like the bus a recording device traveling the open road of what Wolfe calls “the true America” (Wolfe 85). Judgment under these conditions appears an arbitrary imposition, as when I set aside Wolfe and peek into Michael Davidson’s “Tale of Cybernetic Buddhism,” The Karma Machine (1975), a novel I discovered while perusing the shelves of used bookstores during a recent trip to San Francisco. This is a book in which the whole world sleeps, a group of revolutionaries called the Geneva Society having bombarded their fellow humans with “Delta-waves,” so as to prepare a critical operation, a utopian intervention to cure the species of “the disease which afflicts it: mortal fear” (Davidson 104). The revolutionaries pitch this as a “democratic exercise,” as they gather “representatives of the common people” to determine the cure. Heads of state are kidnapped and made to carry out the directives of this “people’s assembly.” One of the revolutionaries, a scientist named Strastnik, tells those gathered, “You are absolutely secure, but you are also completely confined. In brief, you are back in the womb, the womb of history! And you are a new conception! May you prove an immaculate one” (Davidson 105). Before reading further, I set down the book, sit Indian-style and meditate. Vibrant experiences of reciprocity are what I seek in order to feel in a new, delightfully intense way. Experiences of ecstatic contact between self and world. Let love lift us through enlargements of perspective, revealing in this way “the pattern that connects.” Eros, a longing both individuated and attached, free and determined simultaneously. Touching the world and being touched by it in return.