Fantasy is dangerous. The genre has its share of royalists, reactionaries, and racists. Tolkien and Lewis, who taught together at Oxford, were devout Catholics. Writers of the Left sometimes dismiss the genre as ideologically suspect, preferring science fiction in its stead. But no such distinction holds. Science fiction writers of the Left have written works of fantasy, and rightwing fantasists like C.S. Lewis wrote works of science fiction, like the latter’s WWII-era Space Trilogy: Out of the Silent Planet (1938), Perelandra (1943), and That Hideous Strength (1945). Each genre remains anyone’s game.

Tag: Fantasy

Uncle Matt’s New Adventure

“What about Oculus?” wonders the Narrator. “My nephews acquired an Oculus as a ‘family gift’ from Santa this past Christmas,” he explains. VR is here: available for those who can afford it. Off-worlding, world building: that’s what rich people do, rapturing themselves away like rocket scientists. “‘When in Rome…,’” mutters the Narrator, with scare quotes and a shrug.

“I could smoke weed and try it, setting out as Uncle Matt on a new adventure. A portal fantasy inspired by Fraggle Rock.”

Indeed, he could, notes the Author — but does he?

‘Tis a story as much about perception’s limits as about its doors. Writing is the site where an ongoing bodying forth occurs: where forms and objects arrive into the realms of the audible and the visible.

Let imagination have a crack at it, thinks the Narrator. Let us immerse ourselves in fantasies. Let us adopt together the practice of reading works of fantastic literature and watching works of fantastic cinema.

Our approach will be by way of “portal fantasies”: works that involve acts of portage, passage, portation, as through a door or gate connecting previously distinct worlds. The OED defines a portal as “A door, gate, doorway or gateway, of stately or elaborate construction.” The term enters English by way of French and Latin with the Pearl Poet’s use of it in the late-fourteenth century. Henry Lovelich uses it soon thereafter in a Middle-English metrical version of a French romance about the Arthurian wizard Merlin. And Milton uses the term in a remarkable passage in Paradise Lost:

Op’n, ye everlasting Gates, they sung,

Op’n, ye Heav’ns, your living dores; let in

The great Creator from his work returnd

Magnificent, his Six Days work, a World;

Op’n, and henceforth oft; for God will deigne

To visit oft the dwellings of just Men

Delighted, and with frequent intercourse

Thither will send his winged Messengers

On errands of supernal Grace. So sung

The glorious Train ascending: He through Heav’n,

That op’nd wide her blazing Portals, led

To Gods Eternal house direct the way,

A broad and ample rode, whose dust is Gold

And pavement Starrs, as Starrs to thee appear,

Seen in the Galaxie, that Milkie way

Which nightly as a circling Zone thou seest

Pouderd with Starrs.

Note how Heaven’s gates are “blazing,” as is the world in the first of our readings this semester, Margaret Cavendish’s The Blazing World. Cavendish and Milton were contemporaries. Cavendish published The Description of a New World, Called The Blazing World in 1666. Paradise Lost appeared one year later.

Orpheus in Hades’ Lounge

There’s a parking, a journeying outward. Up and out we launch past West End Mill Works, off on tonight’s adventure, beginning with an evening stroll. Graffiti marks the spot. Stream to one side of us, water rushing over rocks. Spotify shifts from Steely Dan’s “King of the World” to Jan Hammer Group’s “Don’t You Know,” voices and cars in the distance. Looking both ways, we cross the street and rush down onto a shaded path through a nearby park, crickets singing in parallax with Neil Young’s “Computer Age.” We turn off the song and continue for a moment in silence. Upon arrival to a crossroads, we ask of each other (like Ginsberg to Whitman in Ginsberg’s “A Supermarket in California”), “Which way now?” Looking up, we rise and step proudly toward pink clouds. Conversation turns toward Old & Used Books as we pass a graffiti-clad muffler shop. Bulldog with paintbrush arrives as comic relief — reality for a moment a goofy animal fable whodunit. We grab beers as day turns to night. Ginsberg’s “lights out” reverberates, hangs in the air after us having heard earlier in the day Let’s Active’s “Orpheus in Hades’ Lounge,” featuring hometown hero Mitch Easter.

Can Orpheus be told anew? We recall to each other the character’s many forms. Jean Cocteau’s Orpheus (1950), Marcel Camus’s Black Orpheus (1959). Also Jean-Paul Sartre’s essay of that name. And let us not forget Samuel R. Delany’s Lo Lobey, the Orphic protagonist at the heart of Delany’s 1967 novel The Einstein Intersection. Hoots is a Hades’ Lounge, is it not, with its red light hanging above its corner booth? So we think as we drink, glorying finally in each other’s presence. “What would happen if our Time Traveler were to stage the scene again?” wonders the Narrator, listening alone now, seated at the same booth many months hence. With “King of the World” still fresh in our ears, members of Steely Dan singing, “No marigolds in the promised land; there’s a hole in the ground where they used to grow,” we restate the refrain of Jan Hammer Group’s “Don’t You Know.” Amid Orpheus wailing away on his flute come the words, “You’re to know that I love you. You’re to know that I care.”

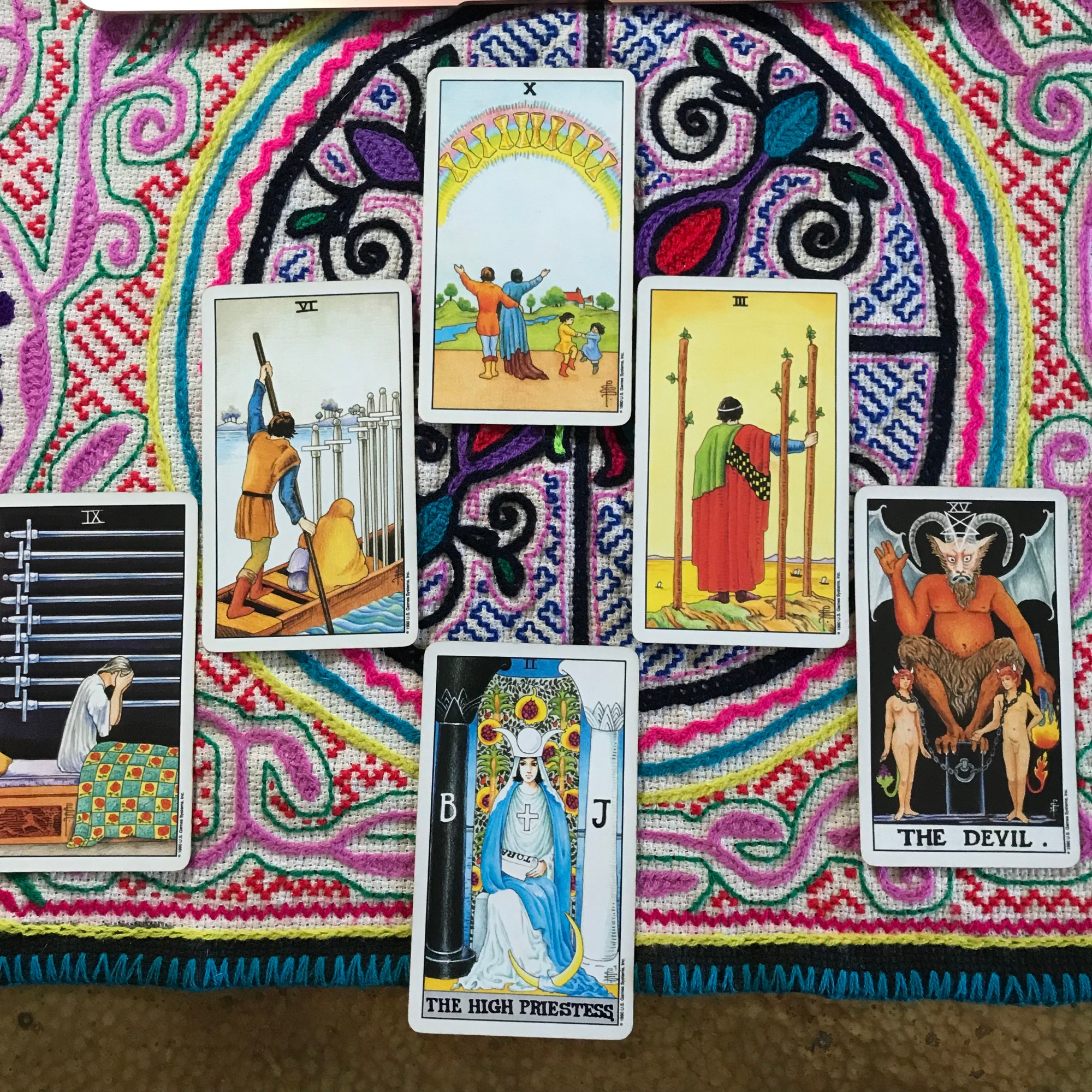

The Spread

Tarot: great modular graphic novel, arranged in a spread and read by super wise super cool Sacred Expanse rock-witch Michelle Mae. I’ve been a fan of hers since 1995, when I saw her band the Make-Up on a bill with Fugazi and Slant 6. Michelle has me set intentions. I share with her my questions for the cards — “What should I be open to? How do I make the best of the year ahead?” — and, upon her instruction, also voice them again silently, eyes closed. She pulls the spread: lays it out on a table, explaining that it can be read both linearly and holistically (i.e., taken as a whole). The two of us then proceed to do so as follows. She introduces the cards one by one, naming them, raising them into my field of vision one at a time, without my knowing at any given point until the end how many there are in total. “Some difficult cards,” she reports. “Two of them major arcana.” Michelle helps me make sense of what she admits with a laugh is a bit of a crazy spread. She sends me afterwards a sacred Tibetan meditation practice, urging me to approach it with utmost respect.

I am to visualize my demons sitting across from me.

I am to ask them what they desire, and I am to feed it to them.

By these means, the instructions suggest, we convert our shadow self into an ally. We become whole again, filled with a sense of power, compassion, and love.

The Session

Mind blown by the experience of seeing musician Michelle Mae’s group The Make-Up perform at Irving Plaza in the spring of 1995, the Narrator had kept up with Michelle’s bands over the years. Never, though, had he met Michelle in person. Life is like that sometimes, especially for those of us with rich fantasy lives. Rarely do we get to sit down one-on-one to converse with the heroes of our youth.

“But early last September,” notes the Narrator, “I did exactly that.”

Thanks to a most excellent gift from his friends, he had the pleasure of meeting with Michelle and working one-on-one with her on Zoom in her capacity as a tarot reader.

She appeared onscreen sitting at a table in her home in Tucson. “I remember noting in the room behind her,” notes the Narrator, “a handcrafted besom leaned upright against a gray stone hearth.”

“There were some difficult cards in my spread,” confessed the Narrator to his friends in the days that followed. “But Michelle is super wise, super cool. She helped me see what the cards might be trying to teach me.”

Severance

“If the texts that students and I have been studying this semester are best referred to as ‘portal fantasies,’” thinks the part of me that persists here in the future, “then that, too, is the term to use in discussing the new AppleTV+ television series Severance. Characters in the show pass quite literally through one or more doors between worlds, living two separate lives.”

The show’s title refers to an imagined corporate procedure of the near-future that severs personhood. Those who volunteer to undergo this procedure emerge from it transformed into split subjects, each with its own distinct stream of memory.

As unlikely as this dystopian premise may seem, we can’t fully distance ourselves from it as viewers, given our severed personhood here “IRL,” or “AFK,” as the kids are fond of saying. “Others may not be quite as manifold as me,” admits the Narrator. “But each of us is Janus-faced. Each of us houses both a waking and a dreaming self, with each incapable of full memory of the other.”

And as the show advances, of course, we learn through a kind of detective work that the severance procedure isn’t in fact what it seems. The work-self (or “innie”) battles the home-self (or “outie”) — as do Superego and Id here at home.

John C. Lilly and the Rats of NIMH

Every time I think of John C. Lilly, who early in his career worked for the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), I’m reminded of Robert C. O’Brien’s 1971 children’s book Mrs. Frisby and the Rats of NIMH. The latter was the source for The Secret of NIMH, a 1982 animated film that captured my imagination as a child.

Jamberry

Jamberry is an audio-visual tone-poem that riffs on the American Dream-State and its history. It sings the raft down the river, the one containing Huck and Jim from Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn — only it follows the raft’s progression (reimagined as a canoe) well beyond Twain’s time. Huck and Jim plunge over a waterfall, enter a time tunnel and drift prophetically past trains into outer space. Moons, rockets: they’re there on the page, Jamberry thus possessing a kind of “space flick plot,” like the one referenced by Black Arts poet David Moore (aka “Amus Mor”) in the opening minutes of Muhal Richard Abrams’s “The Bird Song.” Traveling across time I recall Raistlin Majere, the mage who adventures to the years prior to the Cataclysm in Margaret Weis and Tracy Hickman’s Dragonlance novels. Books that delighted me when I read them as a kid. Afrofuturists like Moore see in the space flick plot a means of escape. Chariots and arkestras part the waters and lead the righteous ones to Zion.

Friday July 2, 2021

Benedict Seymour’s Dead the Ends takes Chris Marker’s La Jetée as its Ur-text. Seymour’s film is a found-footage concoction, and thus incorporates much of the Marker film into itself. But Dead the Ends is also database art, as Seymour pairs these bits of La Jetée with their many echoes in subsequent time travel narratives (Terry Gilliam’s 12 Monkeys, etc.). These works that Seymour reanimates in Dead the Ends all feature romance at their core: lovers seeking each other across time. The narrator of my story, meanwhile, feels growing within himself some similar romantic core. It is there “in the belly of this story,” as Leslie Marmon Silko says of her novel Ceremony. I trance-scribe these texts in the time-stream of the paralogy, but they are words received from another timeline, spoken by a shadow-self whose desires led him West. Or not spoken by the shadow-self, but in dialogue with it. Trance-scribing is not the same as channeling. The shadow-self wants to access the acid diaries of Merry Prankster Stewart Brand, founder of the Whole Earth Catalog. The shadow-self is headstrong — discontented — and then enlivened — reawakened — through an encounter with another. Whereas the paralogical self is a family man: loving father, loving husband. But grown weary from excessive self-silencing, and (given the nature of the karmic cycle) the expectation that he plod on and endure.

Thursday July 1, 2021

All of us are feeling it, the sudden shift in mood and content from one day to the next. Here we are trying to react to this new present. I for one haven’t any words yet for this funk that leaves me driving around weeping to Martha Wainwright midday. I’m supposed to suffer through this, is what I gather from the day’s intel. I’m reliving an incident from my past. Time travel prompts a return of the repressed. I’m here to revisit an old knot of sorrow: a scene of fantasy that ended poorly when pursued in the past. The hope is that in my behaving differently this time, we can heal.