Winograd majors in math at Colorado College in the mid-1960s. After graduation in 1966, he receives a Fulbright, whereupon he pursues another of his interests, language, earning a master’s degree in linguistics at University College London. From there, he applies to MIT, where he takes a class with Noam Chomsky and becomes a star in the school’s famed AI Lab, working directly with Lab luminaries Marvin Minsky and Seymour Papert. During this time, Winograd develops SHRDLU, one of the first programs to grant users the capacity to interact with a computer through a natural-language interface.

“If that doesn’t seem very exciting,” writes Lawrence M. Fisher in a 2017 profile of Winograd for strategy + business, “remember that in 1968 human-computer interaction consisted of punched cards and printouts, with a long wait between input and output. To converse in real time, in English, albeit via teletype, seemed magical, and Papert and Minsky trumpeted Winograd’s achievements. Their stars rose too, and that same year, Minsky was a consultant on Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, which featured natural language interaction with the duplicitous computer HAL.”

Nick Montfort even goes so far as to consider Winograd’s SHRDLU the first work of interactive fiction, predating more established contenders like Will Crowther’s Adventure by several years (Twisty Little Passages, p. 83).

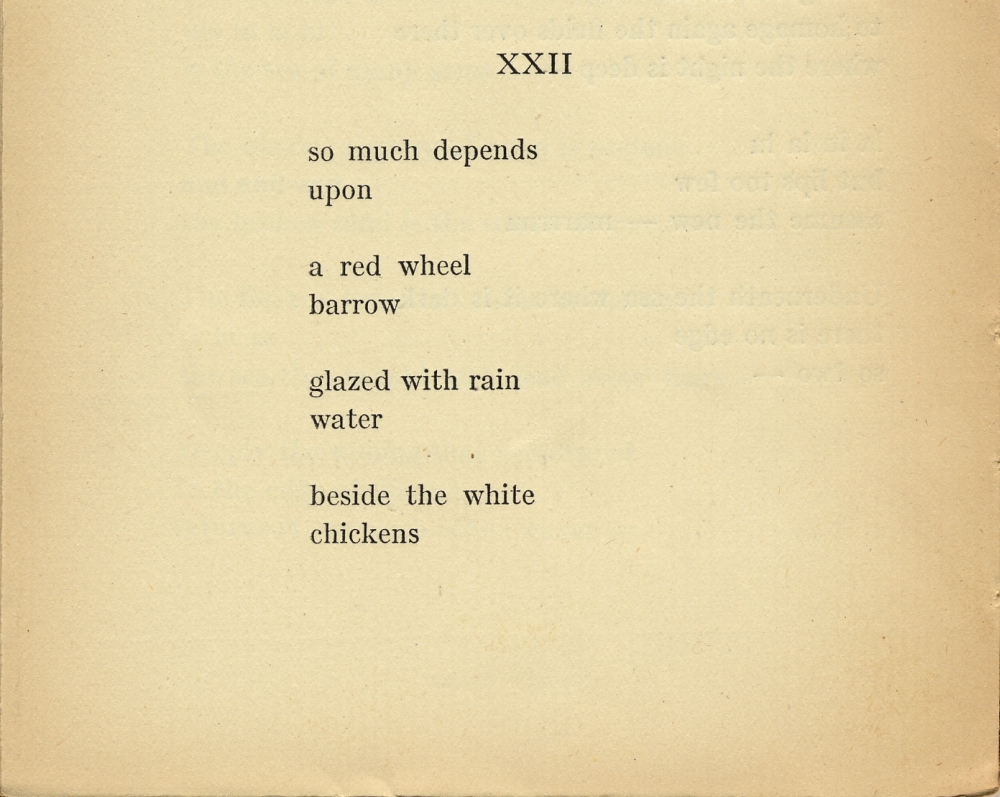

“A work of interactive fiction is a program that simulates a world, understands natural language text input from an interactor and provides a textual reply based on events in the world,” writes Montfort. Offering advice to future makers, he continues by noting, “It makes sense for those seeking to understand IF and those trying to improve their authorship in the form to consider the aspects of world, language understanding, and riddle by looking to architecture, artificial intelligence, and poetry” (First Person, p. 316).

Winograd leaves MIT for Stanford in 1973. While at Stanford, and while consulting for Xerox PARC, Winograd connects with UC-Berkeley philosopher Hubert L. Dreyfus, author of the 1972 book, What Computers Can’t Do: A Critique of Artificial Reason.

Dreyfus, a translator of Heidegger, was one of SHRDLU’s fiercest critics. Worked for a time at MIT. Opponent of Marvin Minsky. For more on Dreyfus, see the 2010 documentary, Being in the World.

Turned by Dreyfus, Winograd transforms into what historian John Markoff calls “the first high-profile deserter from the world of AI.”

Xerox PARC was a major site of innovation during these years. “The Xerox Alto, the first computer with a graphical user interface, was launched in March 1973,” writes Fisher. “Alan Kay had just published a paper describing the Dynabook, the conceptual forerunner of today’s laptop computers. Robert Metcalfe was developing Ethernet, which became the standard for joining PCs in a network.”

“Spacewar,” Stewart Brand’s ethnographic tour of the goings-on at PARC and SAIL, had appeared in Rolling Stone the year prior.

Rescued from prison by the efforts of Amnesty International, Santiago Boy Fernando Flores arrives on the scene in 1976. Together, he and Winograd devote much of the next decade to preparing their 1986 book, Understanding Computers and Cognition.

Years later, a young Peter Thiel attends several of Winograd’s classes at Stanford. Thiel funds Mencius Moldbug, the alt-right thinker Curtis Yarvin, ally of right-accelerationist Nick Land. Yarvin and Land are the thinkers of the Dark Enlightenment.

“How do you navigate an unpredictable, rough adventure, as that’s what life is?” asks Winograd during a talk for the Topos Institute in October 2025. Answer: “Go with the flow.”

Winograd and Flores emphasize care — “tending to what matters” — as a factor that distinguishes humans from AI. In their view, computers and machines are incapable of care.

Evgeny Morozov, meanwhile, regards Flores and the Santiago Boys as Sorcerer’s Apprentices. Citing scholar of fairy tales Jack Zipes, Morozov distinguishes between several iterations of this figure. The outcome of the story varies, explains Zipes. There’s the apprentice who’s humbled by story’s end, as in Fantasia and Frankenstein; and then there’s the “evil” apprentice, the one who steals the tricks of an “evil” sorcerer and escapes unpunished. Morozov sees Flores as an example of the latter.

Caius thinks of the Trump show.