Brand’s words, as always, are worth quoting at length.

“Spacewar as a parable is almost too pat,” he writes. “It was the illegitimate child of the mating of computers and graphic displays. It was part of no one’s grand scheme. It served no grand theory. It was the enthusiasm of irresponsible youngsters. It was disreputably competitive (‘You killed me, Tovar!’). It was an administrative headache. It was merely delightful” (78).

“Yet Spacewar, if anyone cared to notice,” he adds, “was a flawless crystal ball of things to come in computer science and computer use.”

From the game as parable and the parable as crystal ball, Brand extracts eight parameters, eight qualities of Spacewar that have been predictive of things to come:

- It was intensely interactive in real time with the computer.

- It encouraged new programming by the user.

- It bonded human and machine through a responsive broadband interface of live graphics display.

- It served primarily as a communication device between humans.

- It was a game.

- It functioned best on standalone equipment (and disrupted multiple-user equipment).

- It served human interest, not machine. (Spacewar is trivial to a computer.)

- It was delightful.

What about ChatGPT in the 2020s? Is it, too, a “flawless crystal ball,” predictive of things to come?

How quickly it all changes.

Brand publishes “Spacewar: Symbolic Life and Fanatic Death Among the Computer Bums” in the December 7, 1972 issue of Rolling Stone. Videogame journalism: the first of its kind. That same year, Atari manufactures Pong, the arcade sensation, and Magnavox releases the Magnavox Odyssey, the first commercial home video console.

What is Cybersyn’s “control room for technocrats” compared to Brand’s imagined future of “New Games” and personal computing, with its Bay Area rallying cry, “Computers for the people”?

CIA bests Cybersyn in a space war of a deadlier sort the following September.

Chicago Boys playtest neoliberal algorithms in post-coup Chile. Thatcher and Reagan universalize these programs, making them games people play worldwide.

William Gibson refines the “space” of Spacewar, rechristening it “cyberspace” in his novel Neuromancer.

Spacewar is thenceforth the enframing world-picture.

“Gibson contracts the thought of cyberspace from video-game arcades, watching the motor-stimulation feedback loops, self-designing kill patterns. Dark ecstasies in caverns of accelerating pixels. Before virtual reality became dangerous, it was already military simulation,” note Plant and Land in “Cyberpositive.”

Gibson himself has said as much, acknowledging in interviews that he coined the term ‘cyberspace’ after watching teenagers play Atari-era videogames in a Vancouver arcade. “Their posture seemed to indicate that they really, sincerely believed there was something beyond the screen,” he recalls. “I took that home and tried to come up with a name for it.”

“The matrix has its roots in primitive arcade games, in early graphics programs and military experimentation with cranial jacks,” says a voiceover early in Gibson’s novel, the book’s protagonist Case grokking a doc on “cyberspace” from some searchable multimedia encyclopedia of the future. Storying happens by way of a display screen. “On the Sony,” says the narrator, “a two-dimensional space war faded behind a forest of mathematically generated ferns, demonstrating the spatial possibilities of logarithmic spirals; cold blue military footage burned through, lab animals wired into test systems, helmets feeding into fire control circuits of tanks and war planes.” The voiceover returns to describe what we’ve witnessed:

“Cyberspace. A consensual hallucination experienced daily by billions of legitimate operators, in every nation, by children being taught mathematical concepts … A graphic representation of data abstracted from the banks of every computer in the human system. Unthinkable complexity. Lines of light ranged in the non-space of the mind, clusters and constellations of data. Like city lights, receding…” (Gibson 56-57).

“Spacewar serves Earthpeace,” claims Brand. But the “console cowboys” who settle in this new digital frontier are as competitive and combative as their Westworld forebears.

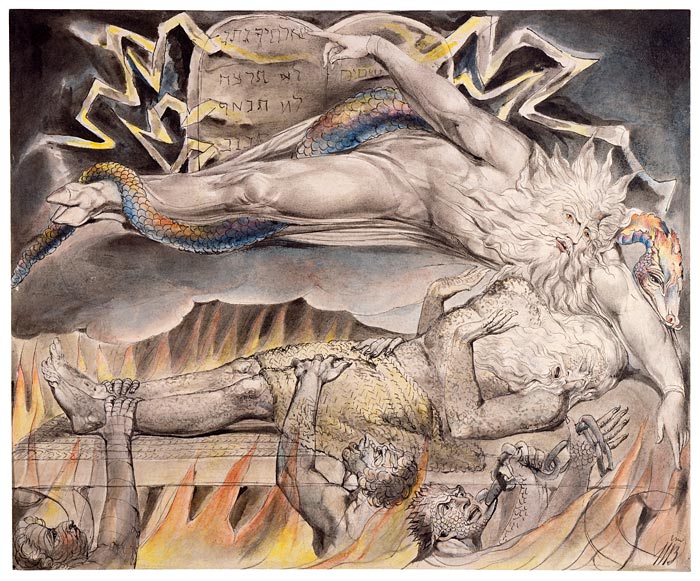

In trying to account for the violence of these visions, Caius thinks of Ernest Callenbach’s 1975 novel Ecotopia. “Imagine a future that works!” exhorts the blurb on the back of the paperback. Technological autonomy won by way of nuclear-armed secession, Silicon Valley erased from the Pacific Northwest of the book’s imagined future — yet even here, amid Ecotopia’s “steady-state system,” aggression remains ineradicable, remedied only by way of ritual war games and sacrificial violence.

“What about the cross?” asks the book’s narrator, an American journalist named Will Weston, observing the way the people of Ecotopia arrange the bloodied body of a man wounded in the games “in a startlingly crucifix-like way” (Callenbach 93).

“Well, Ecotopia came into existence with a Judeo-Christian heritage,” replies an Ecotopian. “We make the best of it” (96).