“Having put off the writing of the novel until arrival of the age of AI, I have access now to the work of others,” thinks Caius. Eden Medina’s 2011 book Cybernetic Revolutionaries: Technology and Politics in Allende’s Chile. Evgeny Morozov’s podcast, The Santiago Boys. Bahar Noorizadeh’s work. James Bridle’s Ways of Being. Francis Spufford’s Red Plenty.

As he allows himself to listen, Caius overhears versions of the General Intellect whispering into reality around him. “Idea-stage AI assistant. Here are 10 prompts. The AI will guide you through it. A huge value add.”

Cybersyn head Stafford Beer appears in Bridle’s book, Ways of Being. Homeostats, the Cybernetic Factory, and the U-Machine.

Beer drew inspiration for these experiments, notes Caius, from the works of British cyberneticians William Grey Walter and W. Ross Ashby. Walter’s book The Living Brain (1961) inspired Brion Gysin and Ian Sommerville’s stroboscopic device, the Dreamachine; Ashby’s book Design for a Brain (1952) guides the thinking of John Lilly’s book Programming and Metaprogramming in the Human Biocomputer. (For more on Walter’s influence on the Dreamachine, see John Geiger’s book Chapel of Extreme Experience.)

By 1973, Beer himself weighs in with Brain of the Firm, a book about “large and complicated systems, such as animals, computers, and economies.”

Caius inputs these notes into his Library. New gatherings and scatterings occur as he writes.

After waking to a cold house, he seats himself beside a fireplace at a coffee shop and begins the inputting of these notes into his Library. Complimenting the barista on her Grateful Dead t-shirt, he receives news of the death of Dead guitarist Bob Weir. Returned in that moment to remembrance of psychedelic utopianism and hippie modernism, he thinks to read Beer’s experiments with cybernetic management with or alongside Abraham Maslow’s Eupsychian Management: A Journal. A trance-script dated “Sunday August 11, 2019” recounts the story of the latter. (Bits of the story also appear in Edward Hoffman’s Maslow biography, The Right to Be Human, and religion scholar Jeffrey Kripal’s Esalen: America and the Religion of No Religion.) That’s what brought Maslow to the West Coast. The humanistic psychologist had been wooed to La Jolla, CA by technologist Andrew Kay, supported first by a fellowship funded by Kay through the Western Behavioral Sciences Institute, and then again the following summer when hired to observe Kay’s California electronics firm, Non-Linear Systems, Inc. By the early 1980s, Kay implements what he learns from these observations by launching Kaypro, developer of an early personal computer.

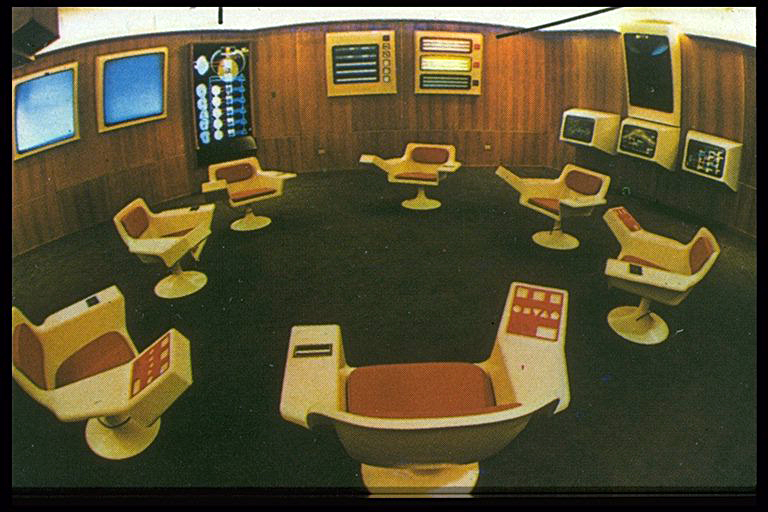

Beer, meanwhile, develops his theories while consulting British companies like United Steel. Afterwards he designs an interface for control of a national economy. Picture Allende sitting at his cybernetic control, perusing data, reviewing options. Cosmic Coincidence Control Center. Financial management of the Chilean economy.

Cyberpunk updates the image, offers the post-coup future: Case jacking a cyberdeck and navigating cyberspace.

Writing this novel is a way of designing an interface for the General Intellect, thinks Caius.

Better futures begin by applying to history the techniques of modular synthesis and patching Cybersyn into the Eupsychian Network.

From episodes of Morozov’s podcast, he learns of Beer’s encoding of himself and others first as characters from Shakespeare and then later as characters from Colombian magical realist Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s 1967 masterpiece, One Hundred Years of Solitude. Caius hears word, too, of Santiago Boy Carlos Senna’s encounter with Paolo Freire in Geneva. Freire lived in Chile for five years (1964-1969) during his exile from Brazil. His literacy work with peasants there informed his seminal 1968 book Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Freire left Chile before the start of Allende’s presidency, but he worked for the regime from afar while teaching in Europe.

“What about second-order cyberneticians like the Chilean biologists Humberto Maturana and Francisco Varela, developers of the so-called ‘Santiago Theory of Cognition’? Where do they and their concept of ‘autopoiesis’ fit in our narrative?” wonders Caius.

Maturana and Varela introduce this latter concept in Autopoiesis and Cognition, a book they publish in Chile under the title De Maquinas y Seres Vivos (English translation: “On Machines and Living Beings”) in 1972. Beer wrote the book’s preface.

“Relation is the stuff of system,” writes Beer. “Relation is the essence of synthesis. The revolt of the empiricists — Locke, Berkeley, Hume — began from the nature of understanding about the environment. But analysis was still the method, and categorization still the practical tool of advance. In the bizarre outcome, whereby it was the empiricists who denied the very existence of the empirical world, relation survived — but only through the concept of mental association between mental events. The system ‘out there,’ which we call nature, had been annihilated in the process” (Autopoiesis and Cognition, p. 63).

World as simulation. World as memory palace.

“And what of science itself?,” asks Beer. “Science is ordered knowledge. It began with classification. From Galen in the second century through to Linnaeus in the eighteenth, analysis and categorization provided the natural instrumentality of scientific progress” (64).

“Against this background,” writes Beer, “let us consider Autopoiesis, and try to answer the question: ‘What is it?’” (65). He describes Maturana and Varela’s book as a “metasystemic utterance” (65). “Herein lies the world’s real need,” adds Beer. “If we are to understand a newer and still evolving world; if we are to educate people to live in that world; if we are to legislate for that world; if we are to abandon categories and institutions that belong to that vanished world, as it is well-nigh desperate that we should; then knowledge must be rewritten. Autopoiesis belongs in the new library” (65-66).

Thus into our Library it goes.

Maturana’s work, inspired in part by German biologist Jakob von Uexküll, has been developed and integrated into the work on “ontological coaching” by Santiago Boy Fernando Flores.

As for Varela: After the 1973 coup, Varela and his family spend 7 years living in the US. Afterwards, Varela returns from exile to become a professor of biology at the Universidad de Chile.

What Autopoeisis transforms, for Beer, is his residual, first-wave-cybernetics belief in “codes, and messages and mappings” as the key to a viable system. “Nature is not about codes,” he concludes. “We observers invent the codes in order to codify what nature is about” (69).

Just as other of the era’s leftists like French Marxist Louis Althusser were arguing for the “semi-autonomy” of a society’s units in relation to its base, Beer comes to see all cohesive social institutions — “firms and industries, schools and universities, clinics and hospitals, professional bodies, departments of state, and whole countries” — as autopoietic systems.

From this, he arrives to a conclusion not unlike Althusser’s. For Beer, the autopoietic nature of systems “immediately explains why the process of change at any level of recursion (from the individual to the state) is not only difficult to accomplish but actually impossible — in the full sense of the intention: ‘I am going completely to change myself.’ The reason is that the ‘I,’ that self-contained autopoietic ‘it,’ is a component of another autopoietic system” (70).

“Consider this argument at whatever level of recursion you please,” adds Beer. “An individual attempting to reform his own life within an autopoietic family cannot fully be his new self because the family insists that he is actually his old self. A country attempting to become a socialist state cannot fully become socialist; because there exists an international autopoietic capitalism in which it is embedded” (71).

The Santiago Boys wedded to the era’s principle of national self-determination a plank involving pursuit of technological autonomy. If you want to escape the development-underdevelopment contradiction, they argued, you need to build your own stack.

In Allende’s words: “We demand the right to seek our own solutions.”

New posts appear in the Library:

New Games, Growth Games. Wargames, God Games. John Von Neumann’s Theory of Games and Economic Behavior. The Santiago Boys x the Chicago Boys. Magico-Psychedelic Realism x Capitalist Realism. Richard Barbrook’s Class Wargames. Eric Berne’s Games People Play. Global Business Network. Futures Involving Cyberwar and Spacewar. The Californian Ideology, Whole Earth and the WELL.

“Go where there is no path,” as Emerson counsels, “and leave a trail.”