Marcuse is among the authors CCRU alum Mark Fisher included on the syllabus for his final course. It was while teaching this course that Fisher took his own life. References to Marcuse appear frequently in Postcapitalist Desire, the compilation of Fisher’s final lectures, gathered and published posthumously by his student Matt Colquhoun. One can only imagine how and in what fashion Marcuse would have fit into Fisher’s book on Acid Communism. It, too, was left unfinished at the time of his death.

Imagine in this book reference to Moten and Harney’s “generativity without reserve.”

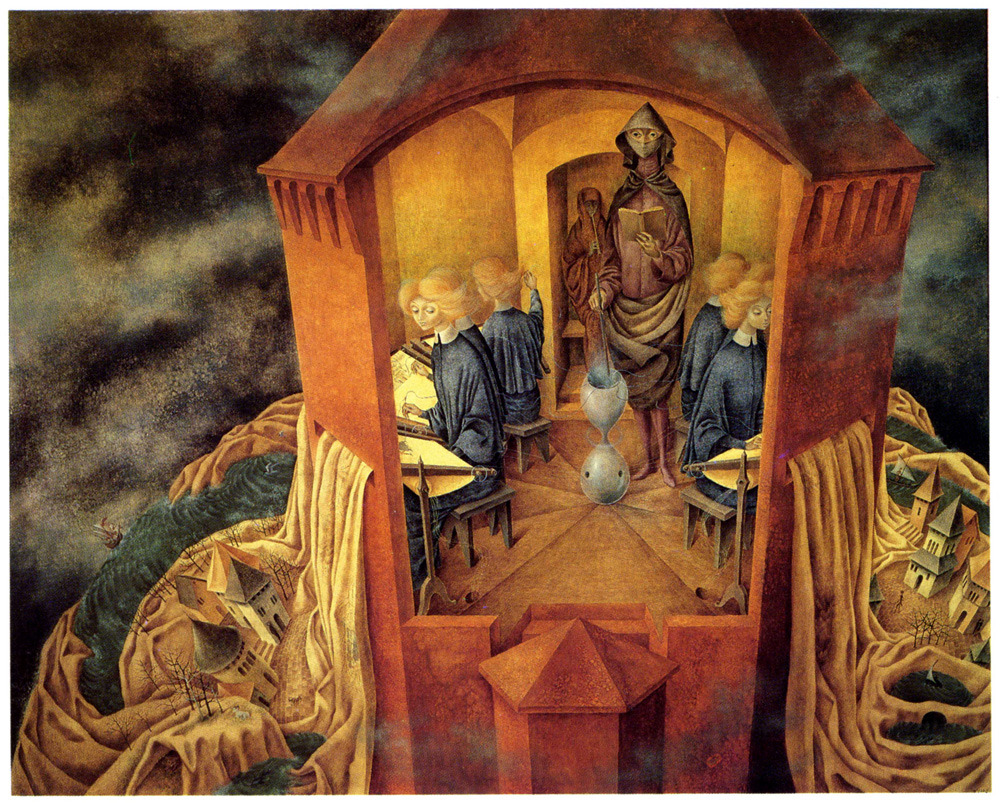

Let us write it here in our Library.

Fisher grew up in a conservative, working-class household in Leicester, a city in the East Midlands region of England. He contributed to CCRU while earning his PhD at University of Warwick in the late 1990s. After teaching for several years as a philosophy lecturer at a further education college, Fisher launched k-punk, a blog dedicated to cultural theory, in 2003.

The ideas that he developed there inform his best-known book, Capitalist Realism, published in 2009.

The book’s title names the ideology-form that dominates life in the wake of the Cold War: “the widespread sense,” as Fisher says, “that not only is capitalism the only viable political and economic system, but also that it is now impossible even to imagine a coherent alternative to it” (Capitalist Realism, p. 2).

Like others on the left, Fisher regards capitalism’s apparent triumph in this moment as a kind of ongoing apocalypse — the opposite of the “Eucatastrophe” anticipated by Tolkien. Fisher describes it not as a miracle, but as “a negative miracle, a malediction which no penitence can ameliorate” (2). “The catastrophe,” as Fisher notes, “is neither waiting down the road, nor has it already happened. Rather, it is being lived through” (2). Everyday life, in other words, as ongoing traumatic event.

Fisher had moved in the year or so before his death to a definition of capitalist realism as a form of “consciousness deflation,” or “the receding of the concept of consciousness from culture.” Forms of consciousness had developed in the 1960s that were dangerous to capital: class consciousness, psychedelic consciousness (key notion being “plasticity of reality”), and (as with early women’s-lib consciousness-raising groups) what we might call personal consciousness (self as it relates to structures). The important and perhaps most controversial point, argues Fisher, is that “Consciousness is immediately transformative, and shifts in consciousness become the basis for other kinds of transformation.” Recognizing the threat this could pose, capitalism adopted a project of Prohibition, or what Fisher called “libidinal engineering and reality engineering.” Consciousness deflation works by causing us to doubt what we feel. Anxiety is enough — that’s all it takes to control us. But consciousness remains malleable, and the tools for raising it continually find their way back into the hands of the people. “What is ideology,” Fisher asked, “but the form of dreaming in which we live?”

Fisher spent the final years of his life as a member of the Department of Visual Cultures at Goldsmiths, University of London. He hanged himself in his home in Felixstowe on January 13, 2017, dead by suicide at the age of 48. He had sought psychiatric treatment in the weeks leading up to his death, but his general practitioner had only been able to offer over-the-phone meetings to discuss a referral.

A few months prior, he’d been lecturing to his students about Marcuse’s Eros and Civilization, championing Marcuse’s book as a reply to the pessimism of Freud’s Civilization and Its Discontents.

Freud’s calculation is that “the price we pay for our advance in civilization is a loss of happiness through the heightening of the sense of guilt” (Civilization and Its Discontents, p. 81). Each of us is made to feel guilty, because in each of us lie impulses in need of repression and disavowal in order for us to produce and perform the duties of civilization. A degree of discontent is thus inevitable in this reckoning. With the compulsion to work comes the triumph of the reality principle over the pleasure principle. Satisfactions deferred, Id repressed by the impossible demands of a Superego without limit: life is ever thus. “One feels inclined to say,” says Freud, “that the intention that man should be ‘happy’ is not included in the plan of ‘Creation’” (23).

“What are the assumptions behind the idea that this level of discomfort is necessary?” asks Fisher. “The assumption is scarcity, fundamentally. That is the fundamental assumption” (Postcapitalist Desire, p. 88).

Are stories and games not the ways we navigate space and time? Capitalist realism is the story-form, the operating system, the game engine Mark felt we’d been made to live within: an aesthetic frame demanding allegiance to a cynical, deflationary realism that organizes history into a kind of tragedy. As with Freud and the Atonists, it insists that, due to scarcity inherent to our nature, we must work in ways that are unpleasurable. Acid Communism rejects this rejection of the possibility of utopia, assuming instead that conscious steerage of stories and games is possible.

Mark finds in Marcuse a remedy to that which blocks utopia: the scarcity mindset that besets those who succumb to capitalist realism.

“The excuse of scarcity, which has justified institutionalized repression since its inception, weakens as man’s knowledge and control over nature enhances the means for fulfilling human needs with a minimum of toil,” writes Marcuse, voicing what Mark hears as an early form of left-accelerationism.

“The still prevailing impoverishment of vast areas of the world is no longer due chiefly to the poverty of human and natural resources but to the manner in which they are distributed and utilized,” adds Marcuse. “But the closer the real possibility of liberating the individual from the constraints once justified by scarcity and immaturity, the greater the need for maintaining and streamlining these constraints lest the established order of domination dissolve. Civilization has to defend itself against the specter of a world which could be free” (Eros and Civilization, p. 93).

Mark lived this struggle for control of the narrative. Yet the game he was playing led to his defeat. Psychedelic intellectuals of the 1960s testified on behalf of a joyous cosmology — yet Mark’s was anything but. For those of us interested in Acid Communism, then, the task now is to invent new games. “Games people play.” Games we can play with others. Careen away from the narrative of identity in space and time imposed by capitalism. Enter, even if only momentarily, a new reality. And then draw others with us into these happenings. Networks of synchronicity, meaning-abundant peaks and plateaus, release from the hegemonic consensus. Trope-scrambling helps, as does appropriation and montage. Let liberation hallelujah jubilee be our rallying cry. And let us welcome as many people as will join us, subtracting prefiguratively into our psychedelically enhanced Acid Communist MMORPG, our free 3D virtual world.

Imagine a conversation there between Fisher and Ishmael Reed. Both wish to refute Freud and his cage of tragedy. What Reed offers, however, and what Mark was perhaps lacking, is a sense of humor.

“LaBas could understand the certain North American Indian tribe reputed to have punished a man for lacking a sense of humor,” writes Reed. “For LaBas, anyone who couldn’t titter a bit was not Afro but most likely a Christian connoting blood, death, and impaled emaciated Jew in excruciation. Nowhere is there an account or portrait of Christ laughing. Like the Marxists who secularized his doctrine, he is always stern, serious and as gloomy as a prison guard. Never does 1 see him laughing until tears appear in his eyes like the roly-poly squint-eyed Buddha guffawing with arms upraised, or certain African loas, Orishas. […]. LaBas believed that when this impostor, this burdensome archetype which afflicted the Afro-American soul, was lifted, a great sigh of relief would go up throughout the land as if the soul was like feet resting in mineral waters after miles of hiking through nails, pebbles, hot coals and prickly things. […]. Christ is so unlike African loas and Orishas, in so many essential ways, that this alien becomes a dangerous intruder in the Afro-American mind, an unwelcome gatecrasher into Ifé, home of the spirits” (Mumbo Jumbo, p. 97).

For Reed, the figure who embodies a potential retro-speculative reconciliation of this conflict is Osiris.