Caius revisits “Both Sides of the Necessary Paradox,” an interview with Gregory Bateson included as the first half of Stewart Brand’s 1974 book II Cybernetic Frontiers. The book’s second half reprints “Spacewar: Fanatic Life and Symbolic Death Among the Computer Bums,” the influential essay on videogames that Jann Wenner commissioned Brand to write for Rolling Stone two years prior.

“I came into cybernetics from preoccupation with biology, world-saving, and mysticism,” writes Brand. “What I found missing was any clear conceptual bonding of cybernetic whole-systems thinking with religious whole-systems thinking. Three years of scanning innumerable books for the Whole Earth Catalog didn’t turn it up,” he adds. “Neither did considerable perusing of the two literatures and taking thought. All I did was increase my conviction that systemic intellectual clarity and moral clarity must reconvene, mingle some notion of what the hell consciousness is and is for, and evoke a shareable self-enhancing ethic of what is sacred, what is right for life” (9).

Yet in summer of 1972, says Brand, a book arrives to begin to fill this gap: Bateson’s Steps to an Ecology of Mind.

Brand brings his knack for New Journalism to the task of interviewing Bateson for Harper’s.

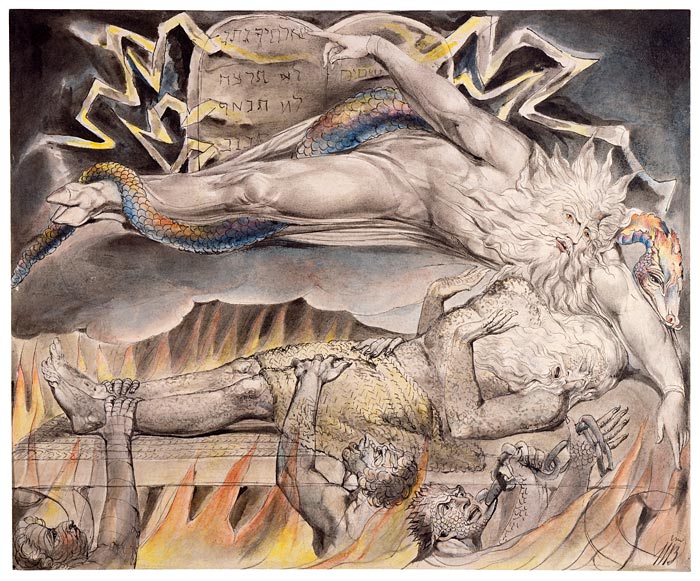

The dialogue between the two reads at many times like one of Bateson’s “metalogues.” An early jag of thought jumps amid pathology, conquest, and the Tao. Reminded of pioneer MIT cybernetician Warren McCulloch’s fascination with “intransitive preference,” Bateson wanders off “rummaging through his library looking for Blake’s illustration of Job affrighted with visions” (20).

Caius is reminded of Norbert Wiener’s reflections on the Book of Job in his 1964 book God and Golem, Inc. For all of these authors, cybernetic situations cast light on religious situations and vice versa.

Caius wonders, too, about the relationship between Bateson’s “double bind” theory of schizophrenia and the theory pursued by Deleuze and Guattari in Capitalism and Schizophrenia.

“Double bind is the term used by Gregory Bateson to describe the simultaneous transmission of two kinds of messages, one of which contradicts the other, as for example the father who says to his son: go ahead, criticize me, but strongly hints that all effective criticism — at least a certain type of criticism — will be very unwelcome. Bateson sees in this phenomenon a particularly schizophrenizing situation,” note Deleuze and Guattari in Anti-Oedipus. They depart from Bateson only in thinking this situation the rule under capitalism rather than the exception. “It seems to us that the double bind, the double impasse,” they write, “is instead a common situation, oedipalizing par excellence. […]. In short, the ‘double bind’ is none other than the whole of Oedipus” (79-80).

God’s response to Job is of this sort.

Brand appends to the transcript of his 1972 interview with Bateson an epilog written in December 1973, three months after the coup in Chile.

Bateson had direct, documented ties to US intelligence. Stationed in China, India, Ceylon, Burma, and Thailand, he produced “mixed psychological and anthropological intelligence” for the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), precursor to CIA, during WWII. Research indicates he maintained connections with CIA-affiliated research networks in the postwar years, participating in LSD studies linked to the MKUltra program in the 1950s. Afterwards he regrets his association with the Agency and its methods.

Asked by Brand about his “psychedelic pedigree,” Bateson replies, “I got Allen Ginsberg his first LSD” (28). A bad trip, notes Caius, resulting in Ginsberg’s poem “Lysergic Acid.” Bateson himself was “turned on to acid by Dr. Harold Abramson, one of the CIA’s chief LSD specialists,” report Martin A. Lee & Bruce Shlain in their book Acid Dreams. Caius wonders if Stafford Beer underwent some similar transformation.

As for Beer, he serves in the British military in India during WWII, and for much of his adult life drives a Rolls-Royce. But then, at the invitation of the Allende regime, Beer travels to Chile and builds Cybersyn. After the coup, he lives in a remote cottage in Wales.

What of him? Cybernetic socialist? Power-centralizing technocrat?

Recognizes workers themselves as the ones best suited to modeling their own places of work.

“What were the features of Beer’s Liberty Machine?” wonders Caius.

Brand’s life, too, includes a stint of military service. Drafted after graduating from Stanford, he served two years with the US army, first as an infantryman and then afterwards as a photographer. Stationed at Fort Dix in New Jersey, Brand becomes involved in the New York art world of those years. He parts ways with the military as soon as the opportunity to do so arises. After his discharge in 1962, Brand participates in some of Allan Kaprow’s “happenings” and, between 1963 and 1966, works as a photographer and technician for USCO.

Amid his travels between East and West coasts during these years, Brand joins up with Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters.

Due to these apprenticeships with the Pranksters and with USCO, Brand arrives early to the nexus formed by the coupling of psychedelics and cybernetics.

“Strobe lights, light projectors, tape decks, stereo speakers, slide sorters — for USCO, the products of technocratic industry served as handy tools for transforming their viewers’ collective mind-set,” writes historian Fred Turner in his 2006 book From Counterculture to Cyberculture: Stewart Brand, the Whole Earth Network, and the Rise of Digital Utopianism. “So did psychedelic drugs. Marijuana and peyote and, later, LSD, offered members of USCO, including Brand, a chance to engage in a mystical experience of togetherness” (Turner 49).

Brand takes acid around the time of his discharge from the military in 1962, when he participates in a legal LSD study overseen by James Fadiman at the International Foundation for Advanced Study in Menlo Park. But he notes that he first met Bateson “briefly in 1960 at the VA Hospital in Palo Alto, California” (II Cybernetic Frontiers, p. 12). Caius finds this curious, and wonders what that meeting entailed. 1960 is also the year when, at the VA Hospital in Menlo Park, Ken Kesey volunteers in the CIA-sponsored drug trials involving LSD that inspire his 1962 novel One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.

Bateson worked for the VA while developing his double bind theory of schizophrenia.

Before that, he’d been married to fellow anthropologist Margaret Mead. He’d also participated in the Macy Conferences, as discussed by N. Katherine Hayles in her book How We Became Posthuman.

Crows screeching in the trees have Caius thinking of condors. He sits, warm, in his sunroom on a cold day, roads lined with snow from a prior day’s storm, thinking about Operation Condor. Described by Morozov as Cybersyn’s “evil twin.” Palantir. Dark Enlightenment. Peter Thiel.

Listening to one of the final episodes of Morozov’s podcast, Caius learns of Brian Eno’s love of Beer’s Brain of the Firm. Bowie and Eno are some of Beer’s most famous fans. Caius remembers Eno’s subsequent work with Brand’s consulting firm, the GBN.

Santiago Boy Fernando Flores is the one who reaches out to Beer, inviting him to head Cybersyn. Given Flores’s status as Allende’s Minister of Finance at the time of the coup, Pinochet’s forces torture him and place him in a prison camp. He remains there for three years. Upon his release, he moves to the Bay Area.

Once in Silicon Valley, Flores works in the computer science department at Stanford. He also obtains a PhD at UC Berkeley, completing a thesis titled Management and Communication in the Office of the Future under the guidance of philosophers Hubert Dreyfus and John Searle.

Flores collaborates during these years with fellow Stanford computer scientist Terry Winograd. The two of them coauthor an influential 1986 book called Understanding Computers and Cognition: A New Foundation for Design. Although they make a bad wager, insisting that computers will never understand natural language (an insistence proven wrong with time), they nevertheless offer refreshing critiques of some of the common assumptions about AI governing research of that era. Drawing upon phenomenology, speech act theory, and Heideggerian philosophy, they redefine computers not as mere symbol manipulators nor as number-crunchers, but as tools for communication and coordination.

Flores builds a program called the Coordinator. Receives flak for “software fascism.”

Winograd’s students include Google cofounders Larry Page and Sergey Brin.