A paper written by Caius for a graduate seminar on “Postmodern Fiction” taught by Dr. Joseph Conte at SUNY-Buffalo, 2005.

Aside from spearheading cyberpunk, William Gibson and Bruce Sterling, co-authors of the 1991 novel The Difference Engine, are also credited for initiating a separate sub-genre of science fiction called “steampunk.” For various critical responses to The Difference Engine, see Jay Clayton’s Charles Dickens in Cyberspace, Joseph Conte’s “The Virtual Reader,” Steffen Hantke’s “Difference Engines and Other Infernal Devices,” Karen Hellekson’s The Alternate History, Nicholas Spencer’s “Rethinking Ambivalence,” and Herbert Sussman’s “Cyberpunk Meets Charles Babbage.”

While Gibson and Sterling’s novel has received a fair amount of attention from critics, subsequent works in the genre for the most part remain unexamined. This paper attempts to pinpoint some of the defining features of steampunk, while also offering a brief commentary on the genre’s relationship to history and postmodernity. I conclude with a few thoughts on the political or ideological underpinnings of the genre, focusing specifically on its relationship to what Fredric Jameson describes as postmodernity’s failure to imagine a compelling future for itself in anything but the most stark and pessimistic of terms. Indeed, dystopian visions (or else visions of an everlasting capitalist present — which, in my opinion, is essentially the same thing) have become a kind of automatic, default setting amongst writers and critics these days. Steampunk narratives ought to be viewed as a logical extension of this trend.

But first, a few comments on the genre itself. Most of the literary and cultural texts collated under the banner of “steampunk” feature speculative narratives set in a Victorian or quasi-Victorian alternate historical universe. Events in these narratives occur in a world that A) vaguely resembles our own recent past — and the past of the Victorian and Edwardian Eras in particular — while B) simultaneously departing from this shared historical reality by way of a signature act of displacement, whereby the technologies that we typically associate with the present are willfully projected backwards. In other words, the standard move of a steampunk narrative is the detailed elaboration of a fictional Victorian universe unexpectedly infiltrated by modern scientific and technological advances actuated by way of what we would otherwise regard to be exemplary nineteenth-century materials and paradigms. Jacquard looms and steam engines become the basis for elaborate mechanical contraptions capable of fulfilling many of the same functions as today’s electrical appliances and personal computers. (Hence the “steam” in “steampunk.”) The result is often highly disorienting: an anachronistic, hybridized fictional space that nonetheless bears some uncanny resemblance to the present.

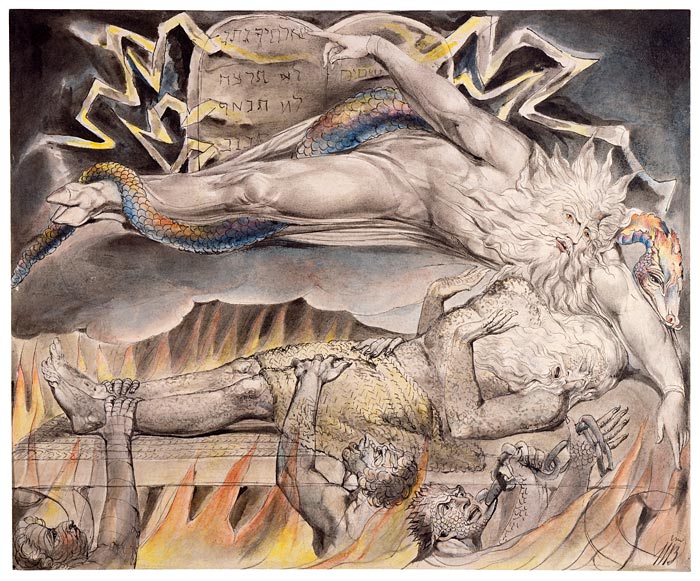

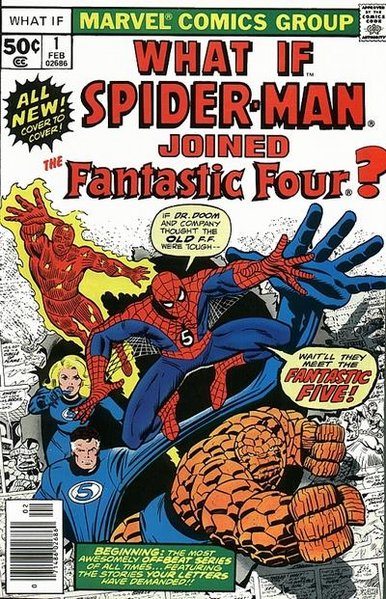

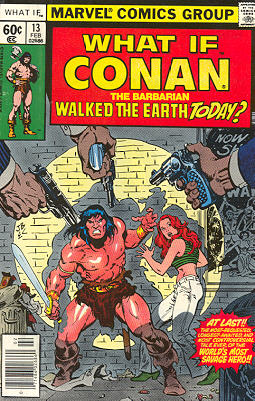

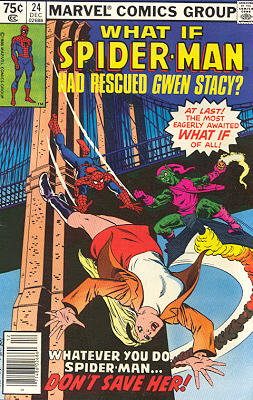

In order to clarify the boundaries and limits of this sub-genre, we can identify at least three main generic predecessors that resemble and maintain an orbit around, while nevertheless remaining distinct from, work classified as “steampunk.” These predecessors include “What If..?” comic books, alternative (and/or counterfactual) histories, and works of historiographic metafiction. Let’s take a few moments to define these genres and to explain their relationship to “steampunk.”

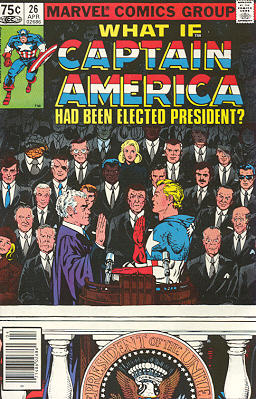

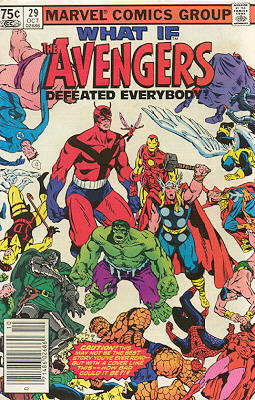

“What If..?” comics are one of the clearest influences on steampunk narratives. Here we have a popular attempt to explore the idea of parallel worlds within a clearly fictitious setting. Beginning in 1977, the Marvel Comics Group released a bimonthly series devoted to dramatizing alternate endings to events within the lives of trademark Marvel characters like Spiderman, Captain America, and the Incredible Hulk. Each issue addresses a “What If..” question dealing with an event in the life of one particular character. Examples of questions posed by each issue include: “What If Spiderman Joined The Fantastic Four?,” “What If Conan the Barbarian Walked The Earth Today?,” “What If Spiderman Had Rescued Gwen Stacy?,” “What If Captain America Had Been Elected President?,” “What If The Avengers Defeated Everybody?,” and “What If The Avengers Had Never Been?”

All of these issues are narrated by a bald, omniscient creature named “Uatu the Watcher.” Uatu stands on the moon and is somehow able to observe all events in all possible worlds. His narratives begin with a singular “bifurcation point” or “point of divergence,” where a dramatic sequence of events from a previous comic book results in a set of consequences different this time around from those that were previously depicted. After identifying this point of divergence, the remainder of Uatu’s narrative extrapolates what would have happened as a result of this changed event.

To this extent, “What If..?” comics are a close relative of that other sub-genre of science fiction known as the “alternative history.” Critics also occasionally refer to works in this sub-genre as “alternate histories,” “allohistories,” or “uchronias.” Historians, meanwhile, hoping to distance themselves from the stigmas of science fiction, have taken to dubbing their own forays in this realm “counterfactuals.” I return to the topic of counterfactuals later in this essay.

The main difference between an alternative history and a “What If..?” comic is that the “What If..?” comic explores a storyline that branches out from the accepted historical trajectory of an already-fictional universe, aka the “Marvel Universe,” whereas an example of “alternative history” would take as its point of departure the history of our world: the world of historical fact.

Philip K. Dick’s novel The Man in the High Castle (1962) is a classic work of “alternative history.” Dick’s novel takes place in a dystopian alternate universe where Giuseppe Zangara succeeds in his effort to assassinate US President-Elect Franklin Delano Roosevelt in February of 1933. Zangara’s actions result in a world where the Axis Powers of Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan emerge victorious at the end of WWII.

The Years of Rice and Salt (2002) by Kim Stanley Robinson is another example of work in this sub-genre. Robinson’s dense, sprawling novel imagines a world where the Black Death of the fourteenth century wipes out a full 99% of the population of medieval Europe. As a result, China and the Islamic world come to dominate the planet over the next seven centuries, while Christianity fades away to become a mere historical footnote.

Other examples of alternative history include classic works of science fiction like Ward Moore’s Bring the Jubilee (1953) and Keith Roberts’ Pavane (1968), as well as more recent novels like Robert Harris’s Fatherland (1993) and Philip Roth’s The Plot Against America (2004).

In many ways, the above examples might suggest that steampunk is simply a particular version of “alternative history.” Like works in the latter genre, steampunk “postulates a fictional event of vast consequences in the past and extrapolates from this event a fictional though historically contingent present or future” (Hantke 246). However, as Steffen Hantke notes, “the most striking examples of alternative histories…do not display as consistent an interest in Victorianism as steampunk does” (246). It is ultimately this fixation with quasi-Victorian settings, along with an abiding interest in alternative technologies, that makes this work seem distinct from other kinds of alternative history.

Aside from “What If..?” comics and alternative histories, the final generic predecessor worth considering in relation to steampunk is that vast body of work that Linda Hutcheon refers to as “historiographic metafiction.” This term is often used to describe books like Robert Coover’s The Public Burning (1977), Ishmael Reed’s Mumbo Jumbo (1972), and E.L. Doctorow’s Ragtime (1975) and The Book of Daniel (1971). Hutcheon defines “historiographic metafiction” as a series of recent novels that are “intensely self-reflective but that also…re-introduce historical context into metafiction and problematize the entire question of historical knowledge” (285-286). In true postmodern fashion, the contradictory effect of such works is both to install and to blur the boundaries between historical and fictional genres.

Although Hutcheon’s definition is probably broad enough (and vague enough) to encompass a novel like The Difference Engine, I think there’s some value in maintaining a distinction between steampunk narratives and historiographic metafiction. After all, a novel like Doctorow’s The Book of Daniel tends to function as a series of speculations meant to supplement history. Additions and corrections are the focus here, rather than the elaboration of deliberately counterfactual scenarios. Doctorow’s fictions, in other words, challenge or cast into doubt certain dominant interpretations of specific historical events (in this case, the Rosenberg trials), often by trying to fill in gaps in the public record. What we end up with is a work of interpretation or commentary.

Steampunk narratives depart from this tradition in the sense that they openly, knowingly contradict the public record. There’s no effort to provide an account of “the way things really were.” At the same time, there’s also no effort to dispute or to call into question the findings of trained historians. Instead, what we have is an explicitly fictional departure from history — an exploration of what could have happened…but most certainly didn’t.

This is precisely the stance toward history that we see at work in a novel like The Difference Engine. While not exactly the first of its kind, Gibson and Sterling’s text is nevertheless the one applauded as the primary inspiration for the term “steampunk” (itself obviously a tongue-in-cheek variant on “cyberpunk,” the sci-fi subgenre that catapulted both authors to fame in the 1980s). What seems most striking about The Difference Engine is its remarkable ability to synthesize all of the various elements that we’ve outlined above.

Like “What If..?” comics and alternative history novels, for instance, the world of The Difference Engine departs from the historical realities of Victorian England by way of a clearly demarcated, singular “point of divergence” — in this case, the successful design and construction of English mathematician Charles Babbage’s famous calculating machine, the Difference Engine, widely acknowledged to have been a precursor of the modern computer. As Gibson and Sterling would have it, this small but momentous adjustment of the historical record results in a world transformed. The Information Age arrives coterminous with the Industrial Revolution, allowing an unholy alliance of scientists and capitalists to harness the productive capacities of steam-driven cybernetic engines in order to advance a ruthless repression of Luddite insurgency and an unprecedented global consolidation of British imperial power.

From historiographic metafiction, meanwhile, the novel borrows the convention of mixing fiction with fact, so that famous historical figures like Babbage, Lord Byron, Ada Lovelace, Karl Marx, travel writer Laurence Oliphant, Texan president Sam Houston, Romantic poet John Keats, two-time British Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli, and biologist T.H. Huxley all jostle for space alongside purely invented characters (as well as figures appropriated from Victorian novels, like Disraeli’s characters, Dandy Mick, Charles Egremont, and Sybil Gerard). This unlikely concoction of narrative strategies has somehow become boilerplate for all subsequent iterations of the steampunk aesthetic.

However, I don’t mean to pose The Difference Engine as some sort of undisputed Ur-text of steampunk. After all, there are certainly a number of steampunk novels that predate Gibson and Sterling’s work by at least a decade, including K.W. Jeter’s Infernal Devices (1987) and Morlock Night (1979). Both of these novels feature retro-Victorian technologies in an alternate historical setting, and Jeter himself is said to have coined the term “steampunk” in an interview from 1987. The Hollywood blockbuster Back to the Future III (1990), meanwhile, has sometimes been seen as a North American frontier variation on the genre. The same can be said for a film like Wild Wild West (1999). Finally, a number of fans and critics have pointed to Walt Disney’s classic film adaptation 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1954), with its retro-Victorian Nautilus submarine, as an important precursor to the genre.

Despite these anticipations, however, most recent examples of steampunk have in fact turned to The Difference Engine as a source of inspiration. Examples of this more recent work include Paul Di Fillipo’s The Steampunk Trilogy (1995); Steampunk: The Role-Playing Game; Neal Stephenson’s The Diamond Age (1995), which has an undeniable steampunk flavor even though it’s set in a neo-Victorian future rather than an alternative past; Alan Moore and Kevin O’Neill’s The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen (2000); the anime film Steamboy (2004), by Katsuhiro Otomo, the director of Akira (1988); and of course the original Steamboy comic book upon which the film is based.

Now, some of this work is clearly an example of what Jameson would call “pastiche” or “blank parody,” where the goal is simply to mimic (or at worst, nostalgically reproduce) the atmosphere and feel of, say, a Jules Verne novel. For instance, audiences often flock to elaborately designed blockbusters like Wild Wild West and Back to the Future III in order to derive pleasure from each film’s stylized echo of the quaintly archaic. Imaginary figures are dressed up in leather chaps and ten-gallon hats and pasted onto a “realistically” staged historical backdrop — and it is precisely this backdrop, this spectacular reconstruction of the “tone and style of a whole epoch” (Jameson 1991, p. 369), that lends each film its novelty and appeal. A similar sense of visual nostalgia seems to permeate Kevin O’Neill’s stunningly rendered illustrations for The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, many panels of which hearken back to the decadent sketches of late-Victorian stylists like Mucha and Aubrey Beardsley. The only element missing from each of these admirably self-conscious allusions is a sense of purpose. This is by-the-books pastiche, as if Jameson’s definition had been mistakenly identified as a checklist. “The imitation of a peculiar or unique style, the wearing of a stylistic mask, speech in a dead language” (Jameson 1998, p. 5): it’s all here. One hunts around looking desperately for the scare quotes, only to come back empty-handed. This is arguably steampunk at its worst.

But I think it would be wrong to apply these claims to the genre as a whole. Books like The Difference Engine, for instance, seem to offer a more critical engagement with their source material (in this case, Disraeli’s Sybil, or, The Two Nations [1845]) than Jameson’s model might allow. An examination of the novel’s genesis and structure, then, is likely to provide us with some insight into the genre’s potential for political commentary. In a rather revealing interview published in Science Fiction Studies just a few months after the release of The Difference Engine, Gibson and Sterling describe their collaborative writing process for the novel as a form of “literary sampling.” As Gibson notes:

[A] great deal of the intimate texture of this book derives from the fact that it’s an enormous collage of little pieces of forgotten Victorian textual material which we lifted from Victorian journalism, from Victorian pulp literature […]. Virtually all of the interior descriptions, the descriptions of furnishings, are simply descriptive sections lifted from Victorian literature. Then we worked it, we sort of air-brushed it with the word-processor, we bent it slightly, and brought out eerie blue notes that the original writers could not have. (Fischlin et al 8-9)

At first, this might sound like a recipe for a curious brand of pastiche. But Gibson and Sterling seem to view their work as a critical intervention of some sort: a critique, in particular, of teleology and of liberal ideas of progress. “One of the things that [The Difference Engine] does,” they write, “is to disagree rather violently with the Whig concept of history, which is that history is a process that leads to us, the crown of creation” (Fischlin et al 7). One of the ways that they accomplish this feat is by organizing the novel in a manner that troubles the reader’s ability to form strong identifications with any of its protagonists. The novel itself is divided into five chapters or “iterations,” followed by an appended sixth section entitled “Modus: The Images Tabled.” Each of these first five chapters follows the exploits of one of the novel’s three main characters: a prostitute named Sybil Gerard, a paleontologist named Edward “Leviathan” Mallory, and a diplomat named Laurence Oliphant. The key, of course, is that none of these characters are particularly likeable.

More than half of the book takes the form of a rather conventional, “Indiana Jones”-style adventure yarn, centered around Edward Mallory, his two brothers, and their “heroic” efforts to quell a growing proletarian Luddite insurgency borne in the midst of “The Great Stink,” a vast ecological catastrophe that appears to have engulfed the chaotic streets of London. After joining forces with a detective named Sergeant Fraser, the Mallory brothers proceed to patrol the slums of the East End in a souped-up “steam gurney” called the Zephyr, flexing their technological might against “roving mobs” and “swarthy little half-breeds” (Gibson and Sterling 199), all the while exchanging stories with one another about their various violent imperialist exploits abroad. Before long, Mallory is revealed quite clearly as a misogynist, a racist, and a gun smuggler. He and his macho “band of brothers” succeed in restraining the uprising, but by the end of the novel, we come to learn that Mallory’s counterrevolutionary efforts result not in human betterment. His efforts result, rather, in the creation of a dystopian surveillance state (or a “hot shining necropolis” [428], as the authors would have it) where humans are the mere playthings of some unnamed peering Eye. The effect, of course, is that the Victorian notion of some inexorable march toward progress is turned on its head. Like some weirdly inverted Hegelian “ruse of reason,” the outcome of history is not what its actors assumed.

But despite Gibson and Sterling’s willingness to critically interrogate the so-called “Whig interpretation of history,” their novel ultimately remains ambivalent regarding certain other Victorian attitudes — especially those that deal with women, class, and empire. Indeed, a strange kind of postmodern cynicism casts a shadow across the novel, so that, even though the misogynistic, bourgeois imperial subtexts of Victorian literature are here highlighted and pushed to the foreground, the novel is also simultaneously fierce to eschew the articulation of any positive utopian alternatives. The result is not exactly “blank parody” (although the novel occasionally leans in this direction); instead, we end up with that double-edged, ironic mode of representation that Linda Hutcheon claims “both legitimizes and subverts that which it parodies” (Hutcheon 2002, p. 97). Works of this sort are humorous precisely to the extent that we can distance ourselves from their historically outmoded sentiments and paradigms. But this canned, self-righteous laughter eventually tapers off as we recognize the way our own culture remains deeply implicated in many of these very same paradigms. The only thing lacking from this bold postmodern indictment, then, is a sense of viable political alternatives. Novels like The Difference Engine envision our world at one remove as a nightmarish kind of “dystopia-in-progress”— but they fail to suggest ways to forestall or transcend this fate.

The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen is another work that seems exemplary in this regard. (The following comments deal with the twelve-issue comic book series, which was subsequently gathered together as a two-volume graphic novel, rather than the — to my mind, vastly inferior — Hollywood adaptation.) Both volumes of Moore and O’Neill’s critically acclaimed series feature a pastiche of characters and creatures lifted from the pages of just about every major adventure and science fiction story of the late nineteenth century, including H.G. Wells’ The Time Machine (1895), The Invisible Man (1897), The War of the Worlds (1898), and The Island of Dr. Moreau (1896); H. Rider Haggard’s Allan Quatermain novels; Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897); Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes (1892): Jules Verne’s Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (1870); and Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1886). The comic itself tells the story of a secret five-member crime-fighting unit, the eponymous “League,” formed in 1898 by a British government official named Campion Bond. Members of the group include Mina Murray, Allan Quatermain, Captain Nemo, Dr. Jekyll and/or Mr. Hyde, and Dr. Hawley Griffin (aka The Invisible Man).

Aside from Bond (who is basically a composite of Margery Allingham’s “Albert Campion” and Ian Fleming’s “James Bond”), every other figure in the series — from major protagonists to single-panel throwaways — is an established character from a previous work of fiction. As Moore notes, “We decided that…all characters or names referred to in the strip would have their origins in either fictions written during or before the period in hand, or else in elements from later works that could be retro-engineered into our continuity by the invention of a father, grandfather or other predecessor” (as quoted in Nevins 11).

After the individual members of the League are rounded up from various far-flung peripheries of the Empire, they convene at their headquarters in a secret wing of the British Museum, where Bond instructs them to retrieve a powerful anti-gravity device called the “Cavorite,” stolen from Her Majesty by the ominous Fu Manchu. This reference to Fu Manchu is just the first of the comic’s many sarcastic parodies of the British Empire’s brutal Orientalist ideologies. Toward the end of the second issue of the series, for instance, readers encounter a text box stating, “The next edition of our new Boys’ Picture Monthly will continue this arresting yarn, in which the Empire’s Finest are brought into conflict with the sly Chinee, accompanied by a variety of coloured illustrations from our artist that are sure to prove exciting to the manly, outwardgoing youngster of today.” A similar sensibility is at work in the Editor’s Note to Volume One, where a “Mr. Scotty Smiles” writes:

Greetings, children of vanquished and colonised nations the world o’er. Welcome to this Christmas compendium edition of our exciting picture-periodical for boys and girls. And let us bid a special welcome to those poorer children who, in four or five years time, will be gratefully reading these words in a creased and dog-eared copy of this very publication, its dust jacket torn and several pages in the second chapter stuck together, that has been donated to their orphanage or borstal by local Rotarians. To all such urchins of the future, and to our presumably more well-off, possibly Eton-educated audience of the present day, we wish you many happy fireside hours in the perusal of the thrills and chuckles here contained, though let us not forget the many serious, morally instructive points there are within this narrative: firstly, women are always going on and making a fuss. Secondly, the Chinese are brilliant, but evil. Lastly, laudanum, taken in moderation is good for the eyesight and prevents kidney-stones. With these dictums in mind, allow us to wish both many hours of pictorial reading pleasure, and also the jolliest of Christmas-times to those of you who are not bowed with rickets, currently incarcerated, or Mohammedans. With the Season’s Best Regards, I remain, A friend and confidant to boys everywhere. S. Smiles (Editor).

Once again, as we saw in The Difference Engine, the effect here is not “blank parody” so much as a kind of “knowing complicity” mixed with an ironic sense of distance. Moore and O’Neill deploy exaggerated caricatures of the familiar “Yellow Peril” stereotype (along with occasional offhand remarks about “Mohammedans”), not just to remind readers of the backwardness of these views, but also to make us interrogate our culture’s continuing fascination with racist, hyper-masculine servants of Empire like Quatermain and crew. After all, what is the League if not an allegorical gang of poster children for our ongoing War on Terror?

To state the point as a further set of questions: How or in what ways are steampunk narratives responding to the circumstances shaping the moment of their enunciation? What kinds of individual and collective desires find expression in this type of narrative?

Upon an initial sweep of the field, one might be tempted to explain the appeal of steampunk in terms of its hip, theoretically up-to-date vision of a universe ruled by chance. After all, contingency is something of a buzzword within the academy these days. Historians, for instance, have lately taken to publishing anthologies devoted to what they call “counterfactual experiments.” Examples of this work can be found in Robert Cowley’s What If? and What If? 2, Niall Ferguson’s Virtual History, Nelson W. Polsby’s What If? Explorations in Social-Science Fiction, and Andrew Roberts’ What Might Have Been: Leading Historians on Twelve ‘What Ifs’ of History.

So far, these experiments have remained controversial, with opponents arguing that counterfactuals are simply ideological fictions with no historical merit, calculated to either unnerve or inspire readers. Others object to the kinds of “retrospective wishful thinking” (Ferguson 11) that frequently finds its way into the portrayal of counterfactual scenarios, where authors exercise wisdom that was only made available through hindsight. Defenders of these experiments, meanwhile, often point to the diverse outcomes of two “similar” historical events as proof that history is ultimately ruled by “accident” rather than design — or in other words, that history could have happened differently. Thus What If? anthology editor Robert Cowley tells us, “Much as we like to think otherwise, outcomes are no more certain in history than they are in our own lives. If nothing else, the diverging tracks in the undergrowth of history celebrate the infinity of human options. The road not taken belongs on the map” (Cowley 1999, p. xii).

Counterfactual experiments are therefore presented as evidence in support of contingency. Each scenario is somehow imagined to represent “what would have happened under slightly different circumstances.” The problem, of course, is that individuals clearly never have access to such knowledge. After all, two similar but temporally distinct events is not the same as two versions of the same event. To abstract some hypothetical set of “slightly different circumstances” is to misconceive of the relations and continuities between historical events. All other confusions stem from this initial misconception. As a result, historians involved in counterfactual exercises end up engaging in something like an inverted futurology, or the art of prediction projected backwards. They fail to recognize that the historical event is part of a pure, unrepeatable singularity that can only be perceived in hindsight, and that based on this fact, the methods of laboratory experimentation so central to the production of “laws” of prediction within the natural sciences are ultimately incompatible with the study of history, since historical events are — by their very nature — unrepeatable. Instead, we ought to ask ourselves: wouldn’t the circumstances that gave rise to any particular counterfactual scenario themselves have required an infinite regress of prior circumstances, all “slightly different” from that which came to be? What is the source of “the swerve” or the point of divergence? How does one break with the chain of antecedent causes? One would need to posit some sort of pure, disruptive externality in order for this view to work.

Not surprisingly, these counterfactual “proofs” of contingency are also often presented as covert arguments against Marxism. Andrew Roberts, for instance, editor of a counterfactuals anthology entitled What Might Have Been: Leading Historians on Twelve ‘What Ifs’ of History, proves to be a diehard anticommunist, blathering on in the introduction to his anthology about how “Marxism requires humans to operate according to a predetermined dialectical materialism, and not by the caprices of accident or serendipity” (Roberts 2-3). Apparently Roberts is unfamiliar with the famous statement from the opening of The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Napoleon, where Marx writes, “Man makes his own history, but he does not make it out of whole cloth; he does not make it out of conditions chosen by himself, but out of such as he finds close at hand” (Marx 48). Such a statement implies a theory of history that recognizes the role of contingencies and personalities as one part of an equation that also includes regularities, likelihoods, and long-term structural pressures.

This is not to deny the fact that various Marxist historians like E.H. Carr, E.P. Thompson, and Eric Hobsbawm have each in their own ways offered compelling denunciations of counterfactual history. Thompson even went so far as to toss nasty German words at the phenomenon, referring to counterfactual fictions as “Geschichtswissenschlopff, [or] unhistorical shit” (as quoted in Ferguson 5). But in Roberts’ opinion, “anything that has been condemned by Carr, Thompson, and Hobsbawm must have something to recommend it, especially if on the other side of the argument we have such distinguished supporters and practitioners of the counterfactual technique as Edward Gibbon, Winston Churchill, Thomas Carlyle, Sir Lewis Namier, Hugh Dacre, Harold Nicolson, Isaiah Berlin, Ronald Knox, Emil Ludwig, G.K. Chesterton, H.A.L. Fisher, [and] Conrad Russell” (3).

In fact, conservatives seem to love this sort of thing, often using the counterfactuals genre for purely ideological purposes. Consider the following statement from Cowley, who writes, “Few events have been more dependent on what ifs than the American Revolution. We are the product of a future that might not have been” (Cowley 1999, p. xii). Aside from being flat-out absurd (since, if we subscribe to a belief in contingency, then all events are equally dependent on “what ifs”), Cowley’s statement also serves to promote tired, stock notions of American exceptionalism. Thus, by way of counterfactuals, empires are reminded of their tenuousness as historians play pretend to stave off recognition of the inevitable. The tone is often that of the reminiscent conqueror reflecting back upon his former battles — all “unlikely victories,” of course — and saying, “Damn, that was a close one! Imagine how shitty the world would have been if it wasn’t for my good fortune.” Thus history takes on the appearance of one long series of gambles, winner take all.

And yet, as contemporary Marxists like Jameson have argued, the choice between rigorous necessity and indeterminate contingency is a choice between false gods. The problem is that both of these views pretend to have independent predictive capacities, while simultaneously figuring historical agency as something abstracted from and external to human action. Or, perhaps more accurately: neither of these views is particularly useful on its own as a predictor of the future, since neither view respects our collective capacity to determine the future ourselves. Thus necessity can too often become a nightmare that weighs upon the brains of the living, just as the invocation of contingency can too often come to resemble what Jim Holstun describes as “an exhausted parent responding to a child’s antinomian chorus of ‘Why? Why? Why?’ with the thudding authoritarian coda of ‘Just because’” (30).

Instead, we ought to seek a theory that strikes a balance between these views. Those of us who wish to engage in the art of forecasting should always account for potential contingencies, but this shouldn’t prevent us in any way from drawing upon historical patterns and regularities as a basis for our predictions. Indeed, if Marxists subscribe to some notion of historical “necessity” or inevitability, then this is a notion that is only capable of operating “exclusively after the fact” (Jameson 1971, p. 361). In other words, this is not a view that should have any direct impact on our decisions with regard to the future, since knowledge of necessity is only born in retrospect (or, as Hegel once noted, “the owl of Minerva only flies at night”).

Unfortunately, like their counterfactual cousins, steampunk narratives are nothing if not contingent. The overwhelming sense that one gets from a book like The Difference Engine is that history could have gone either way — or any number of ways, for that matter. And yet, for all of their alleged contingency (figured most directly in terms of fashions and technologies), steampunk narratives prefer to have it both ways. They insist upon the contingency of a period’s fashions only in order to imbue other historical processes with a sense of pure necessity. Readers are able to recognize historical divergences in these works only because their changes unfold against an otherwise familiar backdrop. Take The Difference Engine, for instance. The convulsive transformation of society wrought by the emergence of the computer comes to assume a kind of doubly-inscribed sense of inevitability, so that whether it’s now or later, computers will change our lives, and there’s nothing any of us can do about it. And of course, for all of its avowed allegiance to a kind of “choose-your-own-adventure” version of history, the alternative past of The Difference Engine can still only lead to dystopia. It is precisely this unexpected shadow of inevitability that hangs over the genre which ought to give us pause as we break out the champagne to celebrate our faith in contingency.

In fact, this same sense of inevitability can also be seen in The Difference Engine’s all-too-easy Cold War conflation of emancipatory socialist visions with incoherent, reactionary Luddite ravings. Thus, in one of the novel’s most important episodes, Edward Mallory arrives at the headquarters of the Luddite agitators where he encounters a self-styled radical who calls himself “the Marquess of Hastings.” Gibson and Sterling appear to have very little sympathy for this character, who they portray as an utter hypocrite (and a slaveowner, to boot!), and who immediately brags about having studied the works of Karl Marx and William Collins, along with “the utopian doctrines of Professor Coleridge and Reverend Wordsworth” of the Susquehanna Phalanstery (Gibson and Sterling 291). From this immersion in Marx’s work, the Marquess concludes that “some dire violence has been done to the true and natural course of historical development” (Gibson and Sterling 301). Mallory blanches at the sound of this baldly teleological vision, and responds by shouting, “History works by Catastrophe! It’s the way of the world, the only way there is, has been, or ever will be. There is no history — there is only contingency!” (301). He then clubs the Marquess over the head with the butt of a pistol, knocking the man unconscious. Afterwards, as if to make sure readers got the message, Gibson and Sterling have Jupiter, the Marquess’s “Negro” slave, tell Mallory, “You were right, sir, and he was quite wrong. There is nothing to history. No progress, no justice. There is nothing but random horror” (302). In one fell swoop, then, Marxism is dismissed in exemplary Cold War fashion as a misguided theory of history touted by slaveowners, Luddites, and thugs — and in its place, of course, we’re offered “nothing but random horror.”

By way of conclusion, then, I would like to suggest that this all has something to do with our society’s ongoing failure to imagine the future. One is reminded of Jameson’s famous claim in The Seeds of Time, where he writes, “It seems to be easier for us today to imagine the thoroughgoing deterioration of the earth and of nature than the breakdown of late capitalism; perhaps this is due to some weakness in our imaginations” (xii). Jameson elaborates on this notion of an ongoing failure of the utopian imagination in the “Introduction” to his book, Archaeologies of the Future, where he writes:

It is not only the invincible universality of capitalism which is at issue […]. What is crippling is not the presence of an enemy but rather the universal belief, not only that this tendency is irreversible, but that the historic alternatives to capitalism have been proven unviable and impossible, and that no other socioeconomic system is conceivable, let alone practically available. The Utopians not only offer to conceive of such alternate systems; Utopian form is itself a representational meditation on radical difference, radical otherness, and on the systemic nature of the social totality, to the point where one cannot imagine any fundamental change in our social existence which has not first thrown off Utopian visions like so many sparks from a comet. (Jameson 2005, p. xii)

More than anything else, I believe the recent interest in steampunk narratives and alternative histories (at least within the sci-fi community) attests to our society’s peculiar incapacity to think beyond the dystopian contours of our present historical moment. In many ways, the effort to substitute “steam” in place of the “cyber” in “cyberpunk” is the ultimate form of cultural reverse-engineering. As a result of this act, the future withers before our eyes, replaced by dreams of dirigibles and corsets. I admit: I enjoy reading works like The Difference Engine and The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen — especially in terms of their sly humor and formal ingenuity. I only wish that this exploration of alternative pasts didn’t have to coincide with a decline in utopian thought. Contingency, after all, is a strange kind of freedom when won at the future’s expense.

WORKS CITED:

Clayton, Jay. Charles Dickens in Cyberspace: The Afterlife of the Nineteenth Century in Postmodern Culture. New York: Oxford University Press, 2003.

——. “Hacking the Nineteenth Century.” Victorian Afterlife: Postmodern Culture Rewrites the Nineteenth Century. Eds. John Kucich and Dianne F. Sadoff. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2000.

Conte, Joseph. “The Virtual Reader: Cybernetics and Technocracy in William Gibson and Bruce Sterling’s The Difference Engine.” The Holodeck in the Garden: Science and Technology in Contemporary American Fiction. Eds. Peter Freese and Charles B. Harris. Normal, IL: Dalkey Archive Press, 2004.

Cowley, Robert, ed. What If?: The World’s Foremost Military Historians Imagine What Might Have Been. London: Macmillan, 1999.

——. What If? 2: Eminent Historians Imagine What Might Have Been. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 2001.

Di Filippo, Paul. The Steampunk Trilogy. New York: Four Walls Eight Windows, 1995.

Dyer-Witheford, Nick. Cyber-Marx: Cycles and Circuits of Struggle in High-Technology Capitalism. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1999.

Ferguson, Niall, ed. Virtual History: Alternatives and Counterfactuals. London: Picador, 1997.

Fischlin, Daniel, Veronica Hollinger, and Andrew Taylor. “‘The Charisma Leak’: A Conversation with William Gibson and Bruce Sterling.” Science Fiction Studies 56 (March 1992): 1-16.

Gibson, William and Bruce Sterling. The Difference Engine. New York: Bantam, 1991.

Gunn, Eileen. “The Difference Dictionary.” (2003): <http://www.sff.net/people/gunn/dd/>

Hantke, Steffen. “Difference Engines and Other Infernal Devices: History According to Steampunk.” Extrapolation 40.3 (1999): 244-54.

Hellekson, Karen. The Alternate History: Reconfiguring Historical Time. Kent: Kent State University Press, 2001.

Holstun, James. Ehud’s Dagger: Class Struggle in the English Revolution. London: Verso, 2000.

Hutcheon, Linda. “‘The Pastime of Past Time’: Fiction, History, Historiographic Metafiction.” GENRE XX (Fall- Winter 1987).

——. The Politics of Postmodernism (Second Edition). London: Routledge, 2002.

Jameson, Fredric. Archaeologies of the Future: The Desire Called Utopia and Other Science Fictions. London: Verso, 2005.

——. Marxism and Form: Twentieth-Century Dialectical Theories of Literature. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1971.

——. Postmodernism, or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism. Durham: Duke University Press, 1991.

——. The Seeds of Time. New York: Columbia University Press, 1994.

Marx, Karl. “The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte.” The Communist Manifesto. Ed. Samuel H. Beer. Arlington Heights: AHM Publishing Corporation, 1955.

Moore, Alan and Kevin O’Neill. The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen: Volume One. La Jolla, CA: America’s Best Comics, 2000.

——. The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen: Volume Two. La Jolla, CA: America’s Best Comics, 2003.

Nevins, Jess. Heroes & Monsters: The Unofficial Companion to The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen. Austin: Monkeybrain Books, 2003.

Polsby, Nelson W., ed. What If? Explorations in Social-Science Fiction. Lexington, MA: The Lewis Publishing Company, 1982.

Roberts, Andrew, ed. What Might Have Been: Leading Historians on Twelve ‘What Ifs’ of History. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2004.

Spencer, Nicholas. “Rethinking Ambivalence: Technopolitics and the Luddites in William Gibson and Bruce Sterling’s ‘The Difference Engine’.” Contemporary Literature 40.3 (Autumn 1999): 403-429.

Sussman, Herbert. “Cyberpunk Meets Charles Babbage: The Difference Engine as Alternative Victorian History.” Victorian Studies 38 (1994): 2-23.